Demand the Impossible

Science Fiction and the Utopian Imagination

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author / editor

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Ralahine Classics

- Introduction to the Classics Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Introduction: The Critical Utopia

- Part One: Theory

- Chapter 2: The Utopian Imagination

- Chapter 3: The Literary Utopia

- Part Two: Texts

- Chapter 4: Joanna Russ, The Female Man

- Chapter 5: Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed

- Chapter 6: Marge Piercy, Woman on the Edge of Time

- Chapter 7: Samuel R. Delany, Triton

- Chapter 8: Conclusion

- Additional Material (2013)

- Chapter 9: “And we are here as on a darkling plain”: Reconsidering Utopia in Huxley’s Island, Tom Moylan

- Chapter 10: Reflections on Demand the Impossible

- Raffaella Baccolini, Introduction

- Lucy Sargisson, A Breath of Fresh Air

- Peter Fitting, Demand the Impossible and the Imagination of a Utopian Alternative

- Andrew Milner, Tom Moylan’s Demand the Impossible

- Lyman Tower Sargent, Miscellaneous Reflections on the “Critical Utopia”

- Kathi Weeks, Timely and Untimely Utopianism

- Gib Prettyman, Extrapolating the Critical Utopia

- Ruth Levitas, We Argue How Else?

- Antonis Balasopoulos, The Negation of Negation: On Demand the Impossible and the Question of Critical Utopia

- Ildney Cavalcanti, Very Inspiring – and Still Highly in Demand

- Phillip E. Wegner, Musings from a Veteran of the Culture Wars; or, Hope Today

- Raffaella Baccolini, Preserving the Dream

- Tom Moylan, A Closing Comment (For Now At Least)

- Notes to the First Edition

- Bibliography of the First Edition

- Index

- Series Index

Ralahine Classics

Utopia has been articulated and theorized for centuries. There is a matrix of commentary, critique, and celebration of utopian thought, writing, and practice that ranges from ancient Greece, into the European middle ages, throughout Asian and indigenous cultures, in Enlightenment thought and in Marxist and anarchist theory, and in the socio-political theories and movements (especially racial, gender, ethnic, sexual, and national liberation; and ecology) of the last two centuries. While thoughtful writing on utopia has long been a part of what Ernst Bloch called our critical cultural heritage, a distinct body of multi- and inter-disciplinary work across the humanities, social sciences, and sciences emerged from the 1950s and 1960s onward under the name of ‘utopian studies’. In the interest of bringing the best of this scholarship to a wider, and new, public, the editors of Ralahine Utopian Studies are committed to identifying key titles that have gone out of print and publishing them in this series as classics in utopian scholarship.

Introduction to the Classics Edition

1.

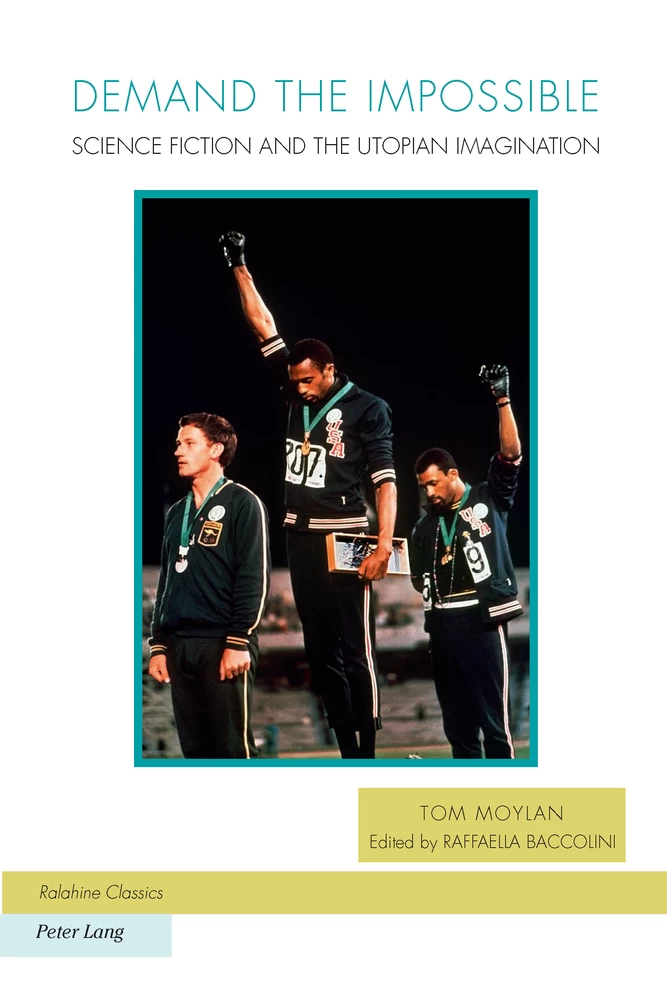

The original cover illustration for Demand the Impossible was a photograph of Oscar Niemeyer’s cathedral in Brasilia. Chosen by my Methuen editor, the image captured an elegant sense of utopian spatiality – with the additional inflection of the postcolonial and, unbeknownst to the editor, an expression of a materialist spirituality that I later came to value. The image for this Ralahine Classics edition could not be more different. Chosen by me this time, this well-known photo of the Black Power salute by Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City more closely captures the direction of my thoughts on the dynamics of the utopian quality of the self-reflexive and self-critical work for a total social transformation that was so central to the politics (and critical utopias) of the late 1960s and 1970s.

The radical action of Smith and Carlos (supported by the silver medal winner, Australian Peter Norman) on the winners’ stand was, for me and many others, a powerful contribution to the social and political opening that was taking place at the time. Carried around the world in that intense image, their act was defiant and hopeful. It signified (theoretically, but also in the sense of witness that term carries in African American culture) and produced a denunciation of the old order of capitalism and imperialism and an annunciation of a new world of justice, equality, and freedom. Grounded in a long history of oppression and reaching out of and beyond that history, Smith and Carlos declared their fidelity to this historical break as well as to the better world that was yet to come. In doing so, they exemplified the contemporary utopian process, as it was lived politically and captured artistically in works such as the ones I wrote about.1

This, then, is not an innocent book (if any ever is). It is not a study developed at a detached distance from its historical time, place, and object of study. While the publication date of the book is 1986 – well after the radical culture of the 1970s and well into the long period of reaction brought about by the Thatcher-Reagan victories and the rising hegemony of neoliberal, global capitalism – I want to make it clear that I did not fundamentally change the substance or tone of the book from the work that resulted from rewriting my doctoral dissertation that was completed in 1981 and two essays that were published in 1980 and 1982. In other words, this is a work of what might be called the “long 70s” and not a work of the later 1980s, and therefore neither nostalgic nor revisionist.

My project developed within the larger context of my life and life in the United States in the late 1960s and 1970s, while I was a teacher in a community college in Waukesha, Wisconsin (able to do so, and even secure tenure, in those days without a PhD or publications) and an activist in an array of left movements and campaigns. My working conditions gave me a steady income and a degree of freedom, of thought and time, not normally known in academia in subsequent years. And so, I took on my doctoral work out of an engaged intellectual desire, and not out of professional need. I began with a dissertation proposal on the general topic of utopia and science fiction in 1973; and from 1974 to 1981 (as a part-time graduate student) I developed my analyses and arguments at the very time the works that I came to call “critical utopias” were being written, published, and read in the United States for the first time: among others, Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed in 1974, Joanna Russ’s The Female Man in 1975, and Samuel R. Delany’s Triton and Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time in 1976.2

Even as it was based in a commitment to produce a carefully researched, thoughtfully considered, and theoretically interrogated study, my project was an unabashedly aligned intervention written during, and sharing in the spirit of, the larger sphere of oppositional culture and politics out of which I saw the critical utopias emerging.3 Recently, Marge Piercy reissued her earliest sf novel: Dance the Eagle to Sleep was published in 1967; it is a near future novel that follows the lives and political struggles of New Left activists of the time. These days I would tend to read it as an early example of what I, along with Raffaella Baccolini and Lyman Tower Sargent, came to call the critical dystopia, but that discussion must wait for another time.4 The reason I mention this work now is that Piercy’s new introduction delivers a heartfelt description of the period and of people’s lives in it. I quote a passage here so as to give readers a refreshed sense of the personal and political culture that, I argue, gave rise to the new utopian works:

It was a period in my life like none other, in which we actually did live in a different way.

Communities were created and thrived for a time. We tried to move past patriarchal marriages and relationships into greater freedom and sometimes it worked. Sometimes it did not. Music was important to us. We waited for new songs as if they were speaking directly to us. We believed in the liberating power of psychedelic drugs with a fervor few would share now. […] We were not as obsessed as people are now with outward appearance. […] We enjoyed our bodies as they were, we danced, we made love, we thrust ourselves into danger. […] If we were sometimes silly and sometimes dismissive of those who did not agree with us, we were also brave and willing to take risks for what we believed in. If we were sometimes mistaken, we also saw the structure of power and property in a way that few do now. We brought up, debated, and sometimes created alternate institutions, dealing with problems that are still critical. We wanted to make a better world, and in some ways, we did. (viii–ix)

Demand therefore was written at the time when that struggle to make a better world was happening quickly and intensely, a time that produced a structure of oppositional, indeed utopian, feeling that not only led to the critical and creative fictions of which I wrote but also shaped the lives of many (including my own). While I gave an occasional graduate seminar presentation on this work, the more meaningful venues wherein I shared and tested my ideas were at Wiscon, the annual sf feminist fan convention held in Madison, and the Summer Institute on Culture and Society organized by the Marxist Literary Group under the leadership of Frederic Jameson and Stanley Aronowitz.

Three streams fed into this work: reading (from childhood onward of sf, political, and historical novels and comic books); activism (especially in terms of the lived relationship between radical change and personal responsibility as it was linked to what I have called the embodied “politics of choice” informing the movements for civil rights, draft resistance, and feminism); and critical theory (beginning with radical Catholic social thought and a secular existentialism with an American beatnik flavor, moving into anarchism and Marxism learned in political study groups, and deepening with the theoretical turn taken by radical Left intellectuals from the 1960s onward (learned primarily from two sources: from 1973, the New German Critique editorial collective led by Jack Zipes – especially with the work of the Frankfurt School, and most especially the “warm stream” represented by Ernst Bloch, Eric Fromm, and Herbert Marcuse – and, from 1976, the Marxist Literary Group Summer Institutes).5

Making sense of this critical utopian tendency in the 1970s was therefore a political as well as a scholarly project. As did others such as Peter Fitting and Bülent Somay, I saw these new science fictional works grow out of the contemporary oppositional culture (anti-capitalist, anti-racist, anti-imperialist; new left, feminist, liberatory, ecological; as well as formally experimental in a way that was only starting to be called “postmodern” by more conservative, anti-political, critics such as Ihab Hassan) and went on to offer critiques of American society and visions of possible alternatives. 6 As such, they constituted a significant shift in political thought and practice and in sf and utopian writing, and accordingly deserved careful attention. In their emphasis on protagonists who become critically aware of their situation and decide to do something about it, I felt that this body of work had an existential and pedagogical potential that spoke to the pressing question of radical political responsibility, of what is to be done, and how it is to be done.

In this regard, I was simultaneously drawn to these works as a political organizer, a teacher, and a scholar. On a meta-theoretical level, these new utopian fictions changed my thinking about utopia (and its history) and furthered my sense of the necessity to regard utopia as a process aiming toward and effecting transformation, but not by way of a fixed blueprint of a new society. Consequently, in what I eventually came to see as an act of theory-as-practice, I wanted to foreground this literary development so that it could be better understood, appreciated, and received. Demand, in other words, is not a post facto elegy for a past moment (written as some have surmised, not surprisingly given its publication date, in the later period of neoliberal reaction) but rather is a contemporaneous and affiliated part of what many of us (fans, activists, writers, teachers, students) valued as cutting edge work at the time of its publication and initial reception.

It seems my objective of bringing this work to a larger audience has more or less been fulfilled. Over the past twenty-eight or so years, Demand has been recognized, disputed, applied, and extended again and again. From what Iߣve seen, the most often quoted segment is that paragraph in which I sum up the critical utopia:

A central concern in the critical utopia is the awareness of the limitations of the utopian tradition, so that these texts reject utopia as a blueprint while preserving it as a dream. Furthermore, the novels dwell on the conflict between the originary world and the utopian society opposed to it so that the process of social change is more directly articulated. Finally, the novels focus on the continuing presence of difference and imperfection within utopian society itself and thus render more recognizable and dynamic alternatives. (Demand 10–11)

I have been glad to see people catching this kernel of my argument – whether they worked with it, against it, or sideways from it. But while many seized on this formal analysis of the critical utopian strategy and especially its emphasis on self-critical, open-ended process, I have often found myself wishing that more would have gone on to tease out the way in which that process figured a new level of engaged activism in the service of a totalizing socio-political transformation (i.e., revolution). While some did, I would have liked to have seen more people additionally citing the lines preceding the above passage, wherein I emphasize the epistemological and political shift to a self-reflexive critique and activism as necessary steps toward an effective, and enduring, transformation:

Thus, utopian writing in the 1970s was saved by its own destruction and transformation into the “critical utopia.” “Critical” in the Enlightenment sense of critique – that is expressions of oppositional thought, unveiling, debunking, of both the genre itself and the historical situation. As well as “critical” in the nuclear sense of the critical mass required to make the necessary explosive reaction. (Demand 10)

For while each of the novels I examined (among others it is important to reiterate) traces the social process of change, in a mainstream or dominant society and in an already existing utopia, each also focuses on the personal journey from passivity to agency in one or several protagonists. It was these existential accounts, in all their variety, that most caught my attention and that I most wanted to emphasize. As I saw it, these tales of awakening and action were the operative mediation between the larger political process and the individual consciousness-raising and agency needed to take radical social change forward. In the textual chapters, I delineate the terrible old worlds and critical new ones of each work, but then I go on to highlight the personal steps of incrementally intensifying praxis required to move toward the utopian horizon (as seen in the storylines of Connie, the four Js, Shevek, Bron, but also Sam, Spider, Lawrence), reading them in terms of what I termed the “ideologeme of the strategy and tactics of revolutionary change” (Demand 45). To be sure, feminist critics such as Lucy Sargisson, Joanna Russ, Fran Bartkowski, and Angelika Bammer have recognized the critical utopian emphasis on process – especially in terms of its relationship to Second Wave feminism and its call for the imbrication of the personal and the political. And Peter Fitting especially recognized the critical utopian focus on the relationship between the politics of everyday life and revolutionary transformation. As he so aptly put it, the critical utopias offered readers “the look and feel and shape and experiences of what an alternative might and could actually be, a thought experiment or form of ‘social dreaming’ […] which gave us a sense of how our lives could be different and better, not only in our immediate material conditions, but in the sense of an entire world or social system” (“Concept” 14–15).7 But not every reader went that far, or was interested in so doing.

Underlying my concern that readers did not catch my aim to delineate these personal/political paths to achieve or to renew utopia (and so to elucidate scenarios of the ways in which people come to know and act in the world in a way that is more engaged and responsible) was my further sense that few picked up on my analysis of the textual structure that produced these narrative trajectories.8 So let me take a moment to restate the distinction I make between the iconic and discrete textual registers that I bring to my analysis of the critical utopias. The original formulation comes from the Russian semiotician, Juri Lotman; but in my case I deployed them in this way:

In examining the utopian text, three operations can be identified: the alternative society, the world, generated in what can be termed the iconic register of the text; the protagonist specific to utopias – that is, the visitor to the utopian society – dealt with in what can be termed the discrete register; and the ideological contestations in the text that brings the cultural artifact back to the contradictions of history. (Demand 36)

As I identified this iconic/discrete structure and its resultant ideological contestation, I was able to describe how these utopian texts (against the usual tendency in sf to privilege the iconic depiction of the alternative world) foregrounded the discrete narrative of agency (the existential trajectory of awareness, action, and change) in the overall textual gestalt. This move enabled me to explain formally how these particular sf works reconfigured the traditional utopian form in a way that spoke to the condition of their times. As I put it a few pages later: “In the new utopia, the primacy of societal alternative over character and plot is reversed, and the alternative society and indeed the original society fall back as settings for the foregrounded political question of the protagonists” (Demand 45). In this refunctioning, I argued, in what is undoubtedly an overstatement, that the received opinion of the “static nature” of the utopian novel as well as the political dead-end encountered by the mainstream realist novel in times of radical political change was rejected. As I put it:

Readers once again find a human subject in action, now no longer an isolated individual monad stuck in one social system but rather a part of the human collective in a time and place of deep historical change. The concerns of this revived, active subject are centered around the ideologeme of the strategy and tactics of revolutionary change at both the micro/personal and macro/societal levels. Furthermore, in the critical utopia the more collective heroes of social transformation are presented off-center and usually as characters who are not dominant, white, heterosexual, chauvinist males but female, gay, nonwhite, and generally operating collectively. (Demand 45)

Later, in The Seeds of Time, Fredric Jameson would distinguish between the nonnarrative form of utopian writing as opposed to the narrative form of dystopia. As he put it: “the dystopia is generally a narrative, which happens to a specific subject or character, whereas the Utopian text is mostly nonnarrative and, I would like to say, somehow without a subject position, although to be sure a tourist-observer flickers through its pages and more than a few anecdotes are disengaged” (Seeds of Time 55–6). While there is much more to be said, and engaged with, concerning what I see as Jameson’s distinction, for my purposes here it resonates with my identification of the iconic register, which corresponds with his sense of nonnarrative utopian form, and the discrete register, which can be understood in terms of the narrative dystopian mode; and yet his distinction does not lead into the specific formal innovation of the critical utopia. With this framework, I therefore work to show how the nonnarrative form of the utopian text is broken open by the more dystopian narrative of a specific subject or character. This, then, is another way of describing the way in which this science fictional tendency of the 1970s succeeded in reviving utopian writing and thinking: by morphing it into a form that drew on both the traditional eutopian evocation of a new spatial reality (complete with its familiar format of voyage, tour, and report – however newly reconfigured in each instance) and the temporal, dystopian, account of personal suffering, systemic discovery, and radical action. This allowed me to speak about the way in which this formal variation facilitated one of the key insights of the oppositional imagination of the time: that (albeit within the contradictions and productivity of the larger structure context) the personal is political, and indeed vice versa.

Finally, I want to make clear that my emphasis on process was never meant to refuse or displace the driving reason for that process: namely, the revolutionary movement toward and achievement of an actually transformed society. Here, while I value and have learned from Ruth Levitas’s important work on the function of utopia in The Concept of Utopia and recently in Utopia as Method, I want to respond to her concern that my emphasis puts too much value on the estrangement effect of the critical process and not enough on the programmatic realization of a utopian society (see Levitas, Method, 110–11). On the contrary, as I tried to clarify above, my original point was precisely that one of the key characteristics of the critical utopias is the attention they give to the necessary relationship between process and the revolutionary production of a new society. I argued that each text examines an existing utopia, but each also delineates the process that is required not only to build that society but also to preserve, revive, and/or refunction the ongoing utopian quality of any post-revolutionary, actually existing, utopia. Therefore, a critical and open process is necessary; but it is not sufficient without a realized and transformed society, even as we must acknowledge that that transformation itself again requires not the stricture of a blueprint but rather an ongoing refunctioning enabled by a self-reflexive and self-critical process. Finally, in my July 2013 contribution to a Round Table discussion on Utopia as Method I added this observation on the historical specificity of the critical utopia:

Prompted by Ruth’s discussion of the critical utopia in light of Miguel Abensour’s argument that there was a political and formal disruption in utopian writing in the 1850s (see Method, 204–9), I would now suggest that we can usefully understand the critical utopia of the 1970s as a formal innovation in a new conjuncture as analogous to but different from the one Abensour locates in the 1850s.9 As such, it is a formal/epistemological expression that restores the importance of the systemic utopia, but does so in a self-critical way. The literary critical utopia of this period is therefore not a postmodern form – although it shares some of the postmodern aesthetic, especially in its self-reflexivity. Rather, it is a product of the cultural logic of an emergent alter-modernity (to borrow Hardt and Negri’s term) that puts more emphasis on a self-aware agency that produces specific systems and then continues to critique and renew them. That is, the social system of a particular critical utopia (as in Piercy or Le Guin) is not simply invoked or imposed but rather produced, challenged, altered, and, most of all, lived by means of the utopian method itself (see Hardt and Negri, Commonwealth, Part 2 especially). I would argue therefore that the critical utopia is itself an exploration in literary form of utopia as method – a thought experiment, if you will, of how utopianism can work – one which has the archaeological, architectural, and ontological elements of which Ruth writes; one which is both heuristic and telic (“Reflections”).

2.

What follows this Introduction is the original edition of Demand. As the text was scanned and then proofread, Raffaella Baccolini and Jack Fennell and I caught some original and new errors; and I admit to changing a few words here and there. But this is the text as it was written then and not as it could have been pulled through all the historical, political, and theoretical twists and turns since the 1970s. Indeed, the biggest semiotic change is the cover.

It is pointless to have regrets about a book, or about anything. But there are a few matters that I want to mention which might go a small distance toward making up for, or at least speaking to, some of the flaws in this work. The first is to acknowledge that this study was, by virtue of my own location and political engagement, focused on works written and read in the US. As I look back now, I can see why some critics have objected to what they understood to be claims and arguments that implied a more global, universalizing, purview (reinforced by my naïve use of the pronoun “we”); however, I never set out to do such a larger study or to make such claims. What I did not do, however, was to specify how my work was specifically, and implicitly, centered on the particularities of US culture and politics, and was both focused and limited because of that; nor did I account for the ways in which my focus on the US occluded the conditions and political developments – and indeed other versions of utopianism – in the rest of the world. The second is to say that I chose four writers out of many, picking them as ones that most intrigued and challenged me as a contemporary reader. As I said above, I was writing out of my own personal and intellectual engagement: I began the entire project as a fan and an active citizen, continued it as a teacher, and only later brought in the methods and skills of a scholar.

Consequently, I did not set out to canonize or valorize this set of texts from a position of high academic culture (or indeed the market), however much my choices may have helped their status and their sales. Rather, I was reading these books as they were being published, and I wanted to make sense of what they meant to me and to share that with others so that they would go on to read them. There were other writers at the time whose work also deserved attention and who I still would include under the rubric of the critical utopia: among them are Suzy McKee Charnas, Sally Gearhart, and Ernest Callenbach; and had I done a larger survey of such works the canonical imperative might have been diffused. Nevertheless, my intention was not to cull these particular texts out of the amazing sf intertext and place them in a privileged enclosure of so-called superior work. Naïvely unaware of the cultural power of academia, I simply, and unabashedly politically, wanted to tell others (as a reader and as a teacher) about these works, which I came to see as part of one tendency among so many others. I wanted to describe and not prescribe their particular form and content, as they were rooted in their time and shared by many. Later, when I was finally turning my dissertation into a book, I was inclined to add a chapter on Aldous Huxley’s Island as a possible precursor to the critical utopias and on Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia as a lateral development, but I never got to them. Looking back, I am sorry I never wrote on these key writers. And I’ve often thought that a chapter on the work of John Brunner, albeit a dystopian writer, would have been important in its own right and would have nicely disturbed the perhaps overbalanced treatment of the four; for I’ve long felt Brunner worked quite creatively in the darker shadows of the critical utopian structure of feeling.10 As a small attempt to rectify these gaps, I append to this edition an essay that I recently wrote, at long last, on Island.11

The closest I come to real regret, and this now becomes a sincere apology to the author, is what I see as my overly harsh (callow? ultra?) criticism of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. I won’t dwell on the conditions or limitations of my analysis of The Dispossessed, but I will refer you to Darren Jorgensen’s useful critique of it, and I will add that I more or less agree with him (even though his assessment still doesn’t fully accord with mine). The truth of the matter is that I have positively taught The Dispossessed more often than any of these four (with Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time coming in a very close second); and in my recent discussions of utopia as method I have repeatedly come back to the figure of Shevek and the Syndicate of Initiative as indicative figurations of the process of radical utopian transformation – a process in which one has, dialectically, to choose both a radical engagement with the world that exists and a steadfast commitment to the transformed horizon.

However critical all utopias may be, these particular works are critical in form and content in a particular way that was emergent at that moment: a moment in which the hegemonic society was being deeply and seriously challenged; a moment in which, to adapt a phrase from a later time, another world was imagined, and lived, as possible; but also a moment in which the utopian impulse that invoked and aimed to produce that world was itself being dialectically interrogated and transformed. In this context, Robert C. Elliott’s The Shape of Utopia (1963) and Henri Lefebvre’s Introduction to Modernity (1962) are good contemporary theoretical expressions of this new direction. As Phil Wegner argues in his Introduction to the Ralahine Classic Edition of Shape, Elliott offered “his ‘prescient’ description of the new critical utopias before the appearance of these texts” in such a way, to use Louis Marin’s concept, that they figure as an “absent referent” in his book (1). And in his critical break with both utopian and Marxist orthodoxy, Lefebvre rejects the utopia of the perfect state or absolute determinism and instead regards utopianism as a radical process of imagination and praxis that is constantly open. And so, by the later 1960s a theoretical and political critical utopianism was being articulated and enacted in dynamic new ways, as seen in these creative variations within sf and in the political processes of the New Left and feminism, especially.

That said, while I still identify the emergence of these works as a distinct formal maneuver within the moment of 1960s–1970s, I welcome more recent research that examines a related critical utopian quality in works published well before the 1960s–1970s and that traces its continuation into the darker, more dystopian years of the neoliberal reaction. In this light, my reading of Huxley’s Island owes a great deal to the analyses provided by Joel Tonyan and Gib Prettyman. Given coincidentally at the same Society for Utopian Studies conference, both authors argue that Island is a critical utopia; whereas I finally came to read Huxley’s novel of the early 1960s in a more anti-utopian light, further emphasizing the cultural and political space that came to be occupied by the critical utopias. Others have stretched the periodizing scope even further. In Imaginary Communities, for example, Wegner argues that “elements of the ‘critical utopia’ are in fact already evident in works produced much earlier in the century,” and he proffers Alexander Bogdanov’s Red Star and Jack London’s The Iron Heel as precursors (99). While Pavla Veselá adopts the category of critical utopia, she then interrogates it and challenges my periodization as she makes a convincing case for designating the work of Sutten E. Griggs and George S. Schuyler, from the 1890s and 1930s respectively, as “precursors” of the critical utopias. And both Simon Guerrier and Michael Kulbucki effectively argue that Iain M. Banks’s series of “Culture” novels can be read as critical utopias – adding to my own conclusion that the work of Kim Stanley Robinson has continued in a critical utopian vein.12

Such extensions or stretching of the periodizing range of the critical utopia have therefore methodologically helped to expand the category of the critical utopia into that of an interpretive, rather than a periodizing, protocol. This can be seen in Prettyman’s and Wegner’s work; and Lyman Tower Sargent has long held that all utopian texts can, in some fashion, be retrospectively read as critical – as have Andrew Milner writing in the Arena “Special Issue on ‘Demanding the Impossible: Utopia and Dystopia’” and several of the authors of a related special issue of Colloquoy. And in her imaginative study of utopia and the garden, making such an interpretive rather than periodizing move, Naomi Jacobs argues that the garden can function like a critical utopia. As she puts it:

To understand one’s garden as a [critical utopia] is to devote all best efforts of mind and body to building a home place that enables and embodies a more perfect relation between the human realm and beings […] of the nonhuman realm. But it is also to remain aware that such an enterprise can never be pure and will never be completed. We so often do too much, or do the wrong thing, in our relation with nature, and yet we can never do enough to honor the wealth and beauty of its gifts. In this, our care of our gardens is much like our care of each other and requires the same kind of humility and gratitude. (168)

Finally, in an argument that moves right into the immediate imbrication of the textual and the political within the processes of the utopian method, Kathi Weeks mobilizes this interpretive protocol to extend the remit of the critical utopian standpoint to such immediately activist forms as the political manifesto (in a reading that moves from Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto to Donna Haraway’s “Manifesto for Cyborgs”) and what she calls the “utopian demand” (e.g., “wages for housework” or “basic income for all”). 13

Details

- Pages

- XXX, 334

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035306101

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035399684

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035399691

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034307529

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0353-0610-1

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (June)

- Keywords

- political culture critical utopia agency

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2014. XXX, 364 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG