Industrial, Science, Technology and Innovation Policies in South Korea and Japan

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part I: Industrial and Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) Policies in Japan and South Korea

- Chapter 1: STI Policies in Japan

- Chapter 2: STI Policies in Korea

- Part II: Science, Technology and Innovation Policies in Japan and Korea

- Chapter 3: STI and Industrial Policies in Korea: Electronics

- Chapter 4: STI and Industrial Policies in Japan: Electronics

- Chapter 5: STI and Industrial Policies in Korea: Medical Devices

- Chapter 6: STI and Industrial Policies in Japan: Medical Devices

- Chapter 7: STI and Industrial Policies in Korea: Aircraft Manufacturing

- Chapter 8: STI and Industrial Policies in Japan: Aircraft Manufacturing

- Chapter 9: STI and Industrial Policies in Korea: Railway Equipment

- Chapter 10: STI and Industrial Policies in Japan: Railway Equipment

This book compares science, technology and innovation policies in Japan and South Korea. Both are industrialized economies; however, Japan is a stagnating power while Korea continues to rise. Moreover, they are in competition with similar export patterns. Thus, policies may be critical in explaining future performance and the course of competition. The comparison of current policies might also shed light on efforts to design policy in other countries.

The two countries have some major characteristics that are similar, such as large populations on relatively small territories with limited natural resources. They have adopted similar policies with a view to rapid industrialization and have oriented their economies towards exports. It should be noted that Korea’s emergence as a global industrial power followed that of Japan.

Background: East Asia and Waves of Industrialization

Modern day industrialization, which began with the first industrial revolution, introduced a major structural break in the world’s economic history. First the UK and then a number of Western European countries industrialized, a process that made them economically and politically powerful on the back of higher economic growth rates and changing economic structures.

Industrialization came in different waves. After the first industrial revolution in the mid-eighteenth century, the second wave came a century later, around the mid-nineteenth century, when countries on different continents started to industrialize. In the Americas, the United States of America; in Europe, Germany; and in Asia, Japan, were the prominent members of this second generation of industrializers. Approximately a century later, in the second half of the twentieth century, the third major wave of industrialization emerged in East Asia, generating the so-called “newly industrialized countries,” as they were first designated by World Bank economists.

Industrialization generated higher incomes and more prosperous societies. It also led to environmental costs, as well as issues with income distribution and workers’ rights. More importantly, the industrialization process brought with it a new and intensifying kind of international and regional competition, as well as interdependencies.

For East Asia, Akamatsu (1962) suggested the “flying geese” pattern to explain both the competition as well as the interdependencies among East Asian ← 13 | 14 → countries, which emanated from rapid industrialization. As an East Asian country industrialized and started to feel wage pressures, lower value-added manufacturing was relocated to neighboring countries, who offered more convenient cost structures and who were willing to industrialize. Thus the East Asian geese moved, with Japan at the head, until the 1990s.

Japan and South Korea: Shifting Fortunes

Since the Meiji period in the second half of the nineteenth century, industrialization and the manufacturing sector have been critical to Japan’s economic survival. Lacking natural and agricultural resources to a large extent, Japan’s economy and its relatively large population have necessitated exports of high value-added manufactures in order to finance imports of raw and intermediate products. That is why Japan has accorded the sustainability of its balance of payments key priority since the Meiji period. Korea is no different in this respect.

More recently, China’s integration into the world economy and Korea’s rapid industrial rise have changed that picture. Since being proclaimed the “number one industrial power of the world” by Vogel (1981), Japan is now struggling macroeconomically as well as industrially. Japan’s bubble economy burst in the mid-1990s, bringing with it macroeconomic problems exacerbated by demographic ones. Moreover, production and sales figures in Japan’s manufacturing sector also show stagnation, although in terms of its technological base and physical industrial assets, the country is still among the world’s front runners. The stagnation of Japan’s manufacturing sector has deep implications for the country, as this sector provides the main exports. Vogel’s top industrial power of the world is not even among the world’s top four exporters anymore.1

In contrast to Japan’s relative decline in manufactures, South Korea is in rapid ascent. Since the 1950s, Korea has pursued industrial policies that have allowed this small, underdeveloped country take its place among the largest industrial powers in the world. This same picture can also be seen in the corporate world; the world’s largest electronics company (by sales) is no longer Sony, but Samsung.

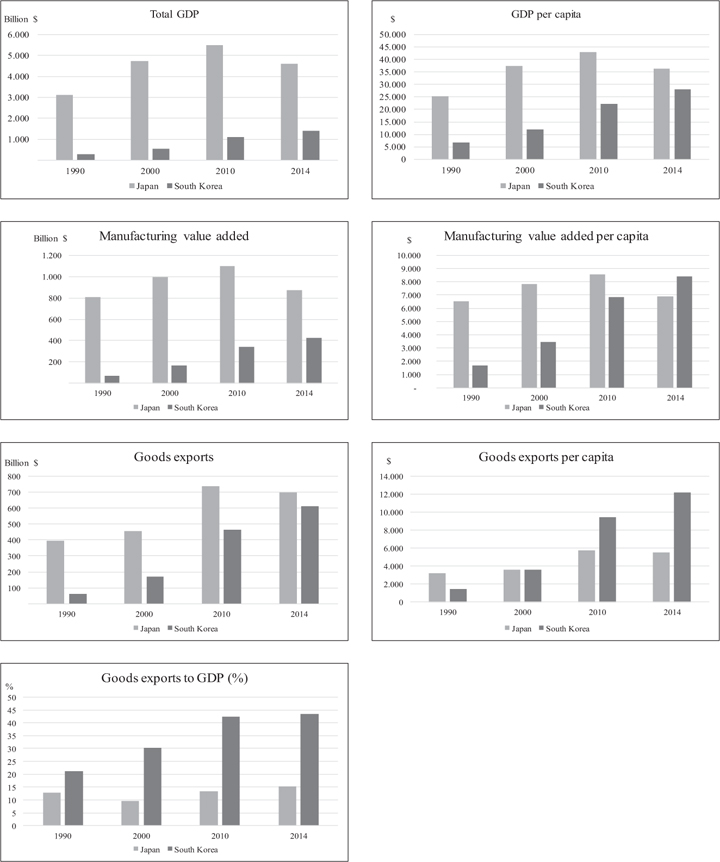

A quick comparison of the performances of the two countries demonstrates that one is rising rapidly, and the other is stagnating, if not failing (Figure 1.0). Overall, the GDP of Japan in US dollar terms has declined in the last few years, ← 14 | 15 → while that of Korea has continued to increase. In terms of per capita income, the two countries are now very close to each other.

The manufacturing value added in Korea has risen continuously over the last decades, and now, value added manufacturing per capita in Korea is higher than that of Japan. This is reflected in terms of exports. The total exports of the two countries are now very close to each other, while Korea’s per capita exports are more than double those of Japan. As a ratio to GDP, Korea’s exports are almost three times those of Japan. Thus, Korea has penetrated the global markets for manufactured goods at an impressive rate. ← 15 | 16 →

Figure 1: Japan and South Korea: A comparison of economic performance2

Industrialization, Technical Progress and Policies

Industrialization and the export of manufactured goods represent the principal sphere contested by Japan and Korea. In understanding the rise of Korea and stagnation of Japan, one has to bear in mind two important factors: technical progress and policies. Industrialization is, after all, a process of technical progress. Countries that have progressed in the industrialization process are those that have managed to build capabilities generating technical progress.

For the two countries, one in ascent on the global scene and the other stagnating (if not declining) in the industrial field, the next immediate question is the role of policies in their development. Japan’s growth and technical progress during the Meiji (1868–1912) and high growth periods (1953–1973) are ascribed to sector-based (sector targeting) industrial policies (e.g. Johnson, 1982; Okimoto, 1989; Wade, 1990), although there is some criticism of this viewpoint (e.g. Krugman, 1994). Korea emulated Japan with a similar choice of interventionist policies (Amsden, 1989); the government very actively pursued sector-based industrial policies that led to rapid industrialization and pushed the country to the forefront of the global industrial market. As with Japan, Korea’s industrial policy has been characterized by selective financial assistance and tax breaks for strategic industries, protection of domestic markets and promotion of exports. Nevertheless, their industrial policies differ with respect to the balance of power between the public and private sectors, the relative size of resources that each government has channeled into its industrial sectors and the scope of these policies.

Today, both countries have exhausted the possibilities of factor accumulation and have reached high levels of technical progress. One would thus be interested in examining their policies regarding science, technology and innovation, as these policies are expected to be the main drivers of total factor productivity in such countries. Both countries have officially ended their industrial policies, but when one considers past sectoral industrial policy as strengthening the capacity of firms in the prioritization of a given sector, we can still see its dominant traces in both countries.

Details

- Pages

- 208

- Publication Year

- 2017

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631703854

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631703861

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653072617

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783631681244

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-07261-7

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (April)

- Keywords

- Industrial Policy Science, Technology and Innovation Railway Equipment Aviation Industry Medical Equipment

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2017. 208 pp., 35 fig., 59 tables