Cognitive Linguistics in the Making

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the Book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- On constructivization – a few remarks on the role of metonymy in grammar

- 1. From proto-language to language as we know it

- 2. Communication based on single words and nonsyntactic concatenation

- 3. Conceptual metonymy constructivized

- 3.1 What a N! Construction

- 3.2 How/What about X Construction

- 3.3 Why not VinfP Construction

- 3.4 One more NP and Clause Construction

- 3.5 If it weren’t for NP, CLAUSE Construction

- Summary

- 4. Constructional metonymy constructivized

- 4.1 English the-Adj Construction

- 4.2 What-if Clause Construction

- 4.3 Monoclausal if-only constructions

- 4.4 Summary

- 5. Conclusions

- References

- A concept of container in temporal phrases – a comparative study

- References

- Subjectivity and objectivity in language as seen by Louis Hjelmslev and Ronald W. Langacker

- 1. Introduction

- 2. “I am under the tree,” or Louis Hjemslev’s interpretation of subjectivity

- 3. Hjelmslev’s account of subjectivity in language vs. Langacker’s approach—similarities and differences

- 4. Conclusion

- References

- A cognitive analysis of spatial particles in Danish ENHEDSFORBINDELSER and corresponding compounds

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Review of literature

- 3. Study

- 3.1 Method

- 3.1.1 Spatial semantics primitives

- 3.1.1.1 Trajector

- 3.1.1.2 Landmark

- 3.1.1.3 Frame of Reference and Viewpoint

- 3.1.1.4 Region

- 3.1.1.5 Path

- 3.1.1.6 Direction

- 3.1.1.7 Motion

- 3.1.2 Prototype, radial set and protoscene

- 3.2 Data presentation

- 3.3 Discussion

- 4. Conclusions

- References

- A cognitive analysis of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its Polish translations: linguistic worldview in translation criticism

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Review of literature

- 2.1 Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its author

- 2.2 Polish translations of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

- 2.3 Linguistic worldview

- 3. Study: method, data presentation and discussion

- 3.1 The analysed translations

- 3.2 The linguistic worldview in the source and target text samples

- 4. Conclusions

- References

- When -ities collide. Virtuality, actuality, reality

- 1. The problem

- 2. Langacker on virtuality vs. actuality

- 3. Langacker on reality

- 4. The derivative world of science fiction

- 5. Conclusions and questions

- References

- Iconicity and the literary text: A cognitive analysis

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Ronald W. Langacker’s subjectification theory

- 3. Imaginal iconicity in poetry and prose

- 4. Diagrammatic iconicity

- 5. In lieu of conclusion: Sorting it all out

- References

- On multiple metonymic mappings in signed languages

- 1. Introduction: signed languages

- 2. Metonymy in phonic and signed communication

- 3. Methodological background

- 4. Multiple metonymic mappings in signed languages

- 4.1 Metonymic chains in single signs

- 4.1.1 The ASL sign for ‘ill/sick’

- 4.1.2 The BSL sign for ‘cricket’ and the ASL sign for ‘baseball’

- 4.1.3 The BSL sign for ‘angling/fishing’

- 4.1.4 The BSL signs for food and drinks

- 4.1.5 The ASL, BSL, and PJM signs for time periods

- 4.2 Multiple metonymies related to category structure in single signs

- 4.2.1 The ASL and BSL signs for ‘milk’

- 4.2.2 The ASL and the PJM signs for ‘medicine’

- 4.2.3 The ASL, BSL, and PJM signs for categories of people

- 4.3 Multiple metonymies in compound signs

- 4.3.1 The BSL sign for ‘babysit, sitter’

- 4.3.2 The PJM signs for ‘boy’ and ‘girl’

- 5. Conclusions

- References

- The metonymic mappings within the event schema in noun-to-verb back-formations

- 1. Introduction

- 2. An overview of the literature

- 2.1 The morphological process of back-formation

- 2.2 Metonymic motivation in English word-formation

- 2.3 Metonymies within the event schema in noun-to-verb back-formations

- 3. Presentation of the study

- 3.1 The AGENT FOR ACTION metonymy

- 3.2 The OBJECT FOR ACTION metonymy

- 3.3 The RESULT FOR ACTION metonymy

- 3.4 The INSTRUMENT FOR ACTION metonymy

- 3.5 The MEANS FOR ACTION metonymy

- 3.6 The DESTINATION/GOAL FOR ACTION metonymy

- 3.7 The TIME FOR ACTION metonymy

- 3.8 The MANNER FOR ACTION metonymy

- 4. Conclusions

- References

- Sources of examples

- The concepts of sleep and death in the Italian language and the unidirectionality of metaphor

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The unidirectionality hypothesis and the basic functions of conceptual metaphor

- 3. Sleep and other states of consciousness

- 3.1 Death is a kind of sleep

- 3.2 Sleep is a kind of death

- 3.3 Cultural links between sleep and death

- 3.4 The unidirectionality hypothesis in the light of the relation between the concepts of sleep and death

- 4. Conclusions

- References

- Sources of examples

- Linguistic Force Dynamics and physics

- 1. Overview

- 2. Linguistic Force Dynamics and naive physics versus modern physics

- 3. The privileged position of the Agonist

- 4. The unequal status of movement and rest

- 5. The greater relative strength of one of the participants

- 6. Schematic reduction

- 7. Schematic reduction excluding the cause of an event

- 8. Blocking, letting, resistance and overcoming

- 9. The intrinsic force tendency of the Agonist

- 10. Summary and Conclusion

- References

- The notion of prototype in linguistics and didactics, revisited

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Prototype in Linguistics

- 3. Prototype in Didactics

- 4. Conclusion

- References

- Using cognitive tools in analysing variant construals: the remakes of “The Scream” by Edvard Munch

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Metonymy

- 3. Imagery

- 4. Blending

- 5. Conclusions

- References

- The metaphor in feedback transfer in L2 acquisition (with some examples of the interaction between the Polish and Lithuanian languages)

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Preliminary overview of the problems

- 3. Feedback transfer and metaphor – theoretical explorations

- 3.1 The concept of feedback transfer

- 3.2 The role of metaphor and its cultural context

- 4. Feedback transfer: short case study

- 4.1 The error of missing the sense of metaphorical/metonymic extension

- 4.2 False friend transfer

- 4.3 Verb transfer with background profiling

- 5. Conclusions

- References

- The process of language acquisition by a child with profound hearing loss and co-existing defects as a contribution to the proposal on the need for a comprehensive approach to the phenomenon of human language capability

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Review of literature

- 3. Case study

- 3.1 Method

- 3.2 Date presentation

- 3.2.1 The patient

- 3.2.2 Treatment and therapy

- 3.2.3 Language development

- 3.2.4 Current cognitive and manual development

- 3.2.5 Discussion

- 4. Conclusion

- References

- Infecting the body politic? Modern and post-modern (ab)use of Immigrants Are Invading Pathogens metaphor in American socio-political discourse

- 1. Introduction

- 1.1 Pathologising the American body politic: a postmodern approach

- 1.2 Cognitive underpinnings of the body politic analogy

- 2. The body politic pathologised: the pre-modern search for the origin of social ills

- 2.1 The Galenic paradigm of internal imbalance versus the proto-microbiological theory and external, „invisible bullets“ of contagion

- 2.2 Pathology or a natural deviation? Functionalist sociology and the ambivalence of contagion.

- 3. Modern American containment discourse

- 3.1 Four paradigms of ethnic adaptation

- 3.2 Failure of the melting pot fantasy and infection scares (19th c. – 1950s)

- 3.3 Post-modern American containment discourse (1950s – current)

- 3.3.1 Cold War and the Soviet contagion

- 3.3.2 War on Terror and the re-emergence of contagion discourse

- 4. Metaphors of social pathology: a scapegoat formula

- 5. Conclusion: why does America fear the foreign contagion?

- References

- A cognitive investigation of the category of sin

- 1. Introduction

- 2. A brief overview of the different approaches to categorization

- 3. Exploring the definition of sin

- 3.1 Sin as defined by the Bible

- 3.2 Sin as defined in Christian theology

- 3.2.1 The Roman Catholic Church (RCC)

- 3.2.2 The Calvinist Church

- 4. The survey

- 4.1 Some methodological considerations

- 4.2 The results of the survey

- 4.2.1 Task 1: The definition of sin

- 4.2.2 Task 2: Prototypical instances of sin

- 4.2.3 Task 5: How “good” are our sins?

- 5. Conclusions

- References

- Linguistic and cultural image of the notion of ‘death’ in Polish and German

- References

- Sources

- ‘Do we always like doing the things that we like to do?’ Non-finite complementation of the verb Like

- Introduction

- The ‘Like –ing’ and ‘Like to-infinitive’ Complement Constructions

- The Usage of ‘Like –ing’ and ‘Like to-infinitive’

- The Scope and Methods of the Analysis

- The Features Related to the Main Verb: Register, Polarity and Agency Hierarchy

- The Features Related to the Complement Verb: Aktionsart, Semantic Field and Transitivity

- Conclusions

- Tools and sources

- References

- What do the Russian prefixes вы-, из- and the preposition из have in common and what makes them different?

- Introduction

- 1. About the preposition из

- 2. The вы- prefix in verbal structures

- The schematic concept of the event starting point

- 3. The prefix из- in verbal structures

- 4. Comparison with Polish

- References

- Sources of examples

- Metonymy and metaphor as merging categories. A study of linguistic expressions referring to the face

- 1. Mental Wholes

- 2. The Theoretical Basis

- 3. The Face in Metonymic and Metaphoric expressions

- 3.1 The Face as a Source Domain

- 4. Conclusions

- References

- Iconicity and (cognitive) grammar: where shall the twain meet?

- Introduction

- 1. Iconicity revisited

- 1.1 Similarity

- 1.2 Taxonomies

- 1.3 Principles

- 2. Seeing, knowing and saying

- 3. Iconicity in grammar

- 3.1 Quantity

- 3.2 Proximity

- 3.3 Sequentiality

- 4. Those mysterious Polish constructions

- 5. Conclusion

- References

- Motion as a modulator of spatiotemporal relations in prepositional expressions of distance

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Semantics of prepositions

- 3. Spatial and temporal meaning of prepositions

- 4. Space and time in PPs expressing spatial distance

- 5. Spatial and temporal representations of distance in the BNC

- 6. Representations of distance with away in the NCP

- 7. Motion as a modulator of distance expressions

- 8. Conclusions

- Appendix

- 1. Explanations for query listings

- 2. Corpus queries used to examine representations of distance in spatial and temporal terms in the BNC.

- 3. Corpus queries used to examine representations of distance in spatial and temporal terms for phrases parallel semantically to the preposition away in the NCP.

- References

- Abstract vs concrete: contrastive analysis of the conceptualization of stillness and motion in Polish and English

- 1. Is abstract motion still abstract?

- 2. Is abstract stillness still abstract?

- 3. Conclusions

- References

- Conceptual-linguistic creativity in poetic texts as a potential source of translation problems

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Review of literature

- 3. Study: method, data presentation and discussion

- a. The method

- b. Data presentation and discussion

- i. The analysis: I Follow Rivers

- ii. The analysis: Midnight Sun

- iii. The analysis: Weltflucht [Escape from the world]

- iv. The analysis: Psalm

- 4. Conclusions

- References

| 11 →

Jan Długosz Academy in Częstochowa, Poland

On constructivization – a few remarks on the role of metonymy in grammar1

Abstract The paper explores the role of conceptual and constructional metonymy in the origins of language. It is argued that the first stage in the development of language, i.e. the stage of Proto-Language was a form of one- and two-word communication relying crucially on the ability to form associations between different participants and relations between them which could be accessed by means of designating single participants or relations alone. I will try to show that that such “non-sentential” forms of communication are also common in modern languages, like Polish and English. Moreover, some relics of those early forms of communication have become parts of entrenched grammatical constructions. There are two basic variants of this general process. In the first variant one or more participants of a relation are ellipsed and accessed metonymically by means of an expression designating either the relation alone or the relation and some of its other participants. In the other variant of this non-sentential communication, it is the constituents designating only single participants of the whole event which metonymically stand for the whole proposition. Finally, it is shown that the same basically metonymic mechanism is instrumental in the formation of dependent monoclausal constructions, which designate complex relations between more than one proposition, such as monoclausal if-only constructions.

Keywords grammatical constructions, proto-language, metonymy, proposition, communication

1. From proto-language to language as we know it

I first hinted at the role of conceptual and constructional metonymy in the origins of language in Bierwiaczonek (2013a). I argued that the first stage in

the development of language, i.e. the stage of Proto-Language, as described by ← 11 | 12 → Bickerton (1990), was a form of one- and two-word communication relying crucially on the ability to form associations between different participants and relations between them which could be accessed by means of designating single participants or relations alone. The process was essentially metonymic in the sense that parts of the communicated messages were used for whole messages. Of course one or two-word (non-syntactic) communication might have worked well in clear contexts; however, the more language was ”displaced”, the more it was necessary to fill the missing contextual information with linguistic information. Thus, more and more words were concatenated; since there was no syntax, however, they were probably arranged according to the general communicative (or processing?) principles, such as

○ Agent First

○ Focus Last

○ Grouping (cf. Jackendoff, 2002)

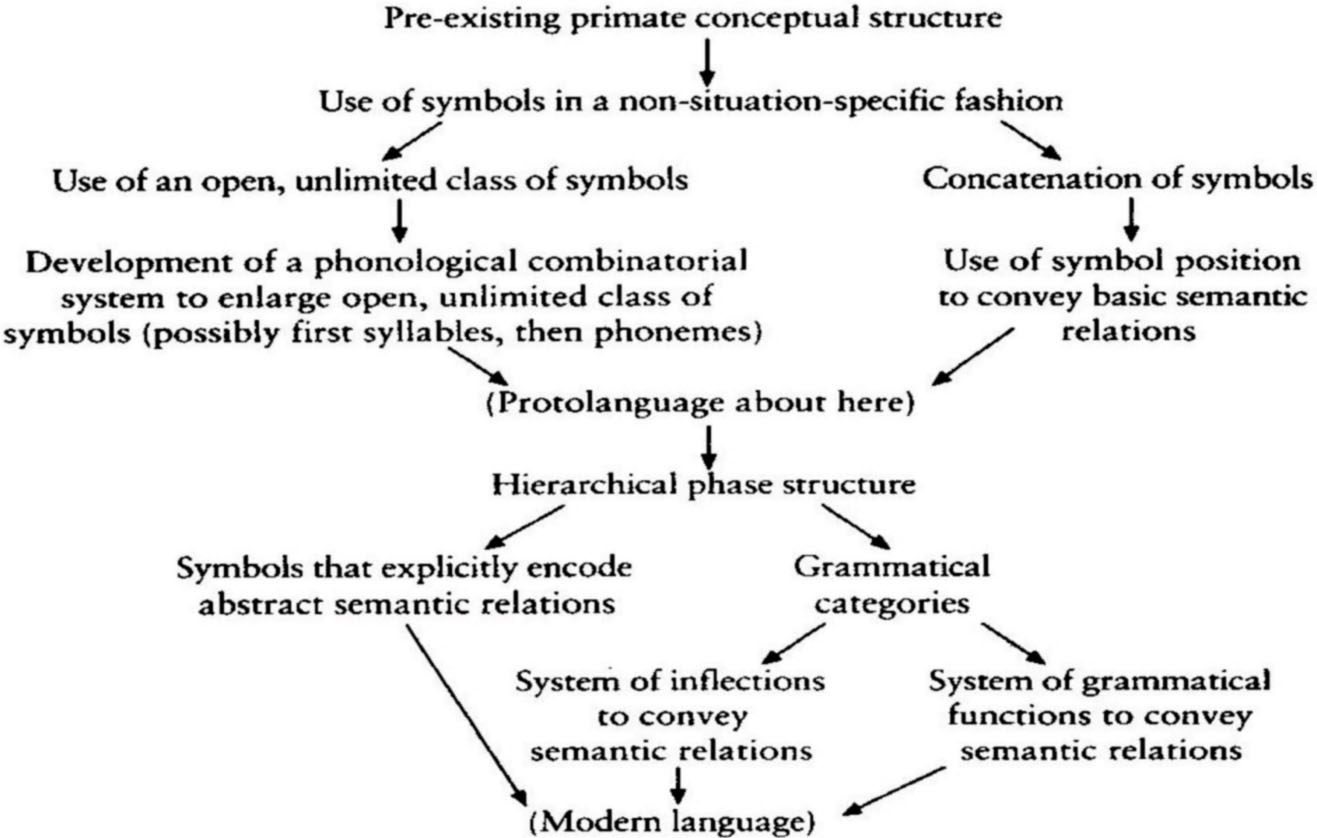

It was probably these first structured complex symbols that in time gave rise to grammatical categories, structural patterns, inflections and grammatical functions paired with conceptual structures of varying degrees of complexity; in short – modern language. According to Jackendoff, the process might have proceeded as follows:

Figure 1: Jackendoff’s theory of origins of language (scanned from Jackendoff 2002:238)

← 12 | 13 →

What adds plausibility to the view of the evolution of language as suggested by Bickerton and Jackendoff is that the same basically metonymic mechanism that enabled our ancestors to communicate in Proto-Language is still used in contexts that are sufficiently rich and, furthermore, that it has crucially contributed to the rise of at least two categories of grammatical constructions: those motivated by conceptual metonymy and those motivated by constructional metonymy. In the following section we shall briefly discuss the traces of those original pre-syntactic communicative behaviours in modern English. In the two other sections we will consider the metonymic sources of a number of much more complex modern grammatical constructions.

2. Communication based on single words and nonsyntactic concatenation

Communication based on single words and non-syntactic concatenation is still a common occurrence. Such communication uses the same original conceptual metonymic mechanism, whereby one (named) part of a conceptual structure stands for a whole complex conceptual structure. It is important that such one-word or two-word combinations should not be confused with holophrases: they designate specific elements of complex conceptual structures which serve as vehicles activate the whole structure (cf. Bickerton, 2003).

Thus, in sufficiently rich contexts complex conceptual structures are often communicated in linguistically short, syntactically functionally unmarked forms.2 For instance, a single proper name, as in (1) below, modulated phonologically can mean [STOP DOING IT, MARK], or [MARK, YOU SHOULD BE ASHAMED OF YOURSELF], or [I CAN’T BELIEVE IT WAS MARK WHO DID IT]. The two infinitives in (2) and (3) in Polish may have full propositional meanings: (2) may well mean [ I WANT YOU TO GIVE ME SOMETHING TO DRINK], while (3), with the rising intonation, would be most likely taken as request for advice, i.e. roughly, [DO YOU THINK I SHOULD GO OR NOT?]. ← 13 | 14 →

In the exchange in (4) the whole story about the weekend can be reduced to elementary concatenation of just and telly, while in the joke in (5), the final puppies effectively and amusingly conveys the whole complex causative conceptual structure.

1) Mark!

2) Pić! (I want you to give me something to drink)

3) Jechać?

4) A: How did you spend the weekend?

B: Just telly

5) Three women were at the doctor’s office for their second trimester check-ups. The first woman, a brunette, said that she was sure that she would have a girl because when she made love to her husband, she was on top! The second affirmed with certainty that she would have a boy, because she was on bottom. The blonde grabbed her head between her hands.

“Oh, crap! Puppies.”

Essentially the same mechanism operates in newspaper and Internet headlines, where single more or less simple concepts stand for often long and complex narratives or reports. Of course the conceptual target of headlines is not exactly known until the story is read, nevertheless, this is the way they are often formed. Here is a sample:

6) BBC Internet headlines:

○ Teen exorcists

○ Human touch

○ Revving up

○ Survivors’ Tales

○ Fighter, stronger

○ White death

○ Stigma and searches

○ Pushing the frontiers

In Bierwiaczonek (2013a) I suggested that this tendency to reduce linguistic form, which Grice included in his Maxim of Manner in the injunction: Be brief, has firm cognitive foundations in our ability to access large conceptual structures by means of their small linguistically designated parts. This Principle of Verbal Economy, as I called it, sounds as follows:

Be brief. Don’t repeat what your addressee(s) already know from their experience and context and make maximal use of their ability to form conceptual associations and construct relevant meaning on the basis of the words they hear, their perception of context, and their knowledge of the world. (Bierwiaczonek 2013a, p. 18) ← 14 | 15 →

Interestingly, PVE has acquired an almost grammatical status in the language of commercial slogans, which are usually accompanied by pictures of their merchandize. A sample of various car makers’ slogans is given below:

7) Slogans:

○ Grace…space…pace (Jaguar)

○ Baseball, hot dogs, apple pie and Chevrolet

○ An American Revolution (Chevrolet)

○ American Luxury (Lincoln)

○ Life, Liberty, and The Pursuit (Cadillac)

○ The power of Dreams (Honda)

○ The Spirit of American Style (Buick)

○ Fuel for the Soul (Pontiac)

○ Unlike any other (Mercedes Benz)

○ For Life (Volvo)

○ Passion for the road (Mazda)

All these expressions are syntactically incomplete, yet in the visual context they successfully communicate complex propositional structures.

3. Conceptual metonymy constructivized

Constructivization of conceptual metonymy is a process whereby a non-sentential structure which designates fragments of the propositional conceptual structure which stands for the whole propositional conceptual structure becomes an entrenched construction of a language. 3 Thus, the results of constructivization of conceptual metonymy are various “non-sentential utterance types” (Culicover and Jackendoff, 2005, Ch. 7) or, as I prefer to call them, non-sentential constructions. 4 Since a good deal of those constructions are systematically used with the same illocutionary force, they constitute an important subset of what I will refer to as “illocutionary constructions”. Let us discuss a few examples. ← 15 | 16 →

3.1 What a N! Construction

The construction What a N!, illustrated by the examples below, is an illocutionary construction, systematically used with the illocutionary force of EXPRESSIVE:

8) What a flower!

9) What a ring!

10) What a shot!

11) What a jump!

In the first two examples the common nouns flower and ring activate a whole evaluative proposition, which in an appropriate context amounts to [I SEE THIS FLOWER/RING AND I THINK IT IS EXTRAORDINARY], so the noun in the construction designates the THEME of the whole proposition. The latter two examples are quite different in that the action nouns designate the dynamic PREDICATE of the proposition, which in turn activates the whole propositional structure whose meaning amounts to [I SAW THIS EVENT AND I THINK THIS X SHOT/JUMPED IN AN EXTRAORDINARY WAY].

Notice that the above construction is idiomatic in that there is no independent productive pattern in English that could be proposed as a regular schema for this construction. The construction represents an interesting case of a non-sentential construction having a “sentential”, propositional meaning.

3.2 How/What about X Construction

Another illocutionary construction which has similar properties to the What a N Construction with an action noun is a subtype of How/What about X Construction with the gerundive VP in the X position, which is often used with the illocutionary force of SUGGESTION (but see Carter and McCarthy, 2006, p. 703f, for other functions as well), illustrated by the BNC examples below:

12) How about bringing him in on Thursday?

13) How about dressing now, Jenny, and coming down-stairs?

14) What about taking me on sometime?

15) What about putting some in the middle?

16) I’m going to have lunch,’ Victor continued, ‘so, as Simon’s otherwise engaged, how about joining me?’

Again, a non-sentential structure designating only the ungrounded (tenseless) Verb Phrase conveys the meaning of the whole proposition. 5 ← 16 | 17 →

The How/What about X Construction is also conceptually metonymic in its other discourse function, namely “to invite someone to speak or comment or to reciprocate a speaking turn” (Carter and McCarty, 2006, p. 704), as in the following exchange borrowed from Carter and McCarthy:

17) A: It was very interesting doing it

B: It was all right was it. Yeah. Yeah. How did everybody else feel? Lucy, how about you?

C: Er, well, the same really. (ibid.)

Whatever B’s question is, it certainly is not about the Addressee’s (Lucy’s) identity but rather about a complex propositional structure concerning her feelings and opinion.

3.3 Why not VinfP Construction

Another non-sentential constructivized way of making tentative SUGGESTIONS is the construction Why not VinfP (cf. Carter and McCarty, 2006, p. 705f), illustrated by the following BNC examples:

18) Why not cut all four at one go?

19) Why not make your visit to the theatre extra special, and spend a night at one of Scarborough’s best hotels?

20) Why not try the opposite setting to the one you’ve just used and see how the needles move (or don’t) in each direction?

Again, the whole propositional content is accessed by the tenseless Verb Phrase.

3.4 One more NP and Clause Construction

Not only predicates but also other constituents and participants or roles they designate may be used to convey full propositional content. For instance, in the One more NP and Clause Construction, as in One more beer and I’m off, the entity designated by X is usually the PATIENT of the whole proposition, construed as a condition or reason for Y, roughly [IF YOU DRINK ONE MORE BEER]. Again, this is an illocutionary construction, with a relatively fixed illocutionary force of THREAT or WARNING (cf. Taylor, 2002, p. 571f). Consider two other BNC examples:

21) One more such blow, I thought, face down in the sand, and I am gone.

22) One more weekend and the security screen could be lifted. ← 17 | 18 →

3.5 If it weren’t for NP, CLAUSE Construction

Another semantically conditional construction motivated by conceptual metonymy, where a single Noun Phrase stands for the whole proposition is If it weren’t for NP, Clause Construction, as in the BNC examples below:

23) If it were not for Section 8 of the Contempt of Court Act, we might be able to make reforms more rationally on the basis of, at least, a minimal sample of the recorded deliberations of informed and unidentified jurors.

24) Ironically, the Great War would not have been the war that it was if it were not for the machine.

25) He also remarked, significantly: If it were not for the Union, I venture to think that women would be all over the London trade.

26) Housewife Rita Davis, of Ilford, Essex, said: ‘We would never have known what our taxes are going on if it was not for The Mirror.’

27) The most popular British cult object, however, has no wheels and would not have moved at all if it was not for British Telecom.

28) If it was not for her, this Council would have had more opportunity of addressing some of the deep problems the Tories either created or left behind.

29) The mammoth catalogue raisonné of Magritte’s work would almost certainly not have come into existence if it were not for John (d. 1973) and Dominique de Menil.

Clearly, the underlined NP-s stand for larger conceptual wholes conveying propositions in which they feature as primary AGENTS or CAUSES responsible for the developments described in the main clause. This conjecture is reinforced by the fact that the construction has also its non-metonymic variety, whereby the whole propositional conceptual structure is conveyed by different kinds of clausal constituents, from full-fledged finite clauses (often introduced by the fact), through relative clauses and gerundive clauses to nominalizations. Consider the following BNC examples:

30) If it were not for the fact that he was one of the favourites you’d have been delighted but as a Gold Cup winner I had to feel a bit disappointed.

Details

- Pages

- 372

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631652008

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653046540

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653985559

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653985566

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-04654-0

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (October)

- Keywords

- Metapher Metonymie raum-zeitliche Beziehungen Ikonizität

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 372 pp., 9 coloured fig., 7 b/w fig., 24 tables, 21 graphs

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG