An early interest in the British Imperial relationship with India prompted my academic focus on the governance of the Raj. How and by what mechanisms was such a vast territory and enormous population efficiently and effectively administered?

Initial research revealed a highly qualified and competent cadre known as the Indian Civil Service. Seen as an elite these young men were specially selected and trained in Britain and sent to India to commence a lifetime career in the various provinces and presidencies. Starting at the bottom of a bureaucratic hierarchy in the various departments of state, which administered India, over time and in accordance with their respective abilities and competence they were able to rise through the ranks to become, at the peak of their careers Governors. Remarkably, these men during the period of the British Raj were few in number and during Sir Harcourt’s time consisted of around 1000 men who administered an Indian population of approximately 300 million in 1900 increasing to 400 million by 1947.

Part of their preparation in Britain involved language training, which facilitated their ability to communicate with the peoples of their provinces. Their initial work in India could involve activity as settlement officers in the rural areas of their provinces, assessing the productivity of land for taxation purposes. This brought them into close contact with farmers and country people, which required fluency in the vernacular. Often, they worked alone travelling over large distances. Thus, in the early stages of their careers they very often developed a familiarity and affection for India and its peoples, particularly in their own provinces. The careers of junior ICS men could involve work in a broad range of departments such as agriculture, health, finance, forestry and others. Proficiency in their duties could see them rise through the ranks to become District Collectors responsible for provincial districts, Commissioners in charge of provincial divisions, Lieutenant Governors and Governors of whole provinces. Interestingly, it was a long-standing convention that only British aristocrats, often with political connection were appointed as Governors by the British Government to the Presidencies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay. This was also the case with appointment as Governor General or Viceroy.

This broadly sets out a background to the framework that the British created and implemented to administer India. However, I found little analysis available in the scholarship, with few exceptions of how this framework actually functioned at its senior levels. What did the ICS and Governors actually do? I found the focus of much contemporary research and scholarship on British India tends to be focused on Indian nationalism and its relationship with the Viceroy and the British Government. I could find very little written about the Governors of British India and their function (and thus the supporting function of the administrative hierarchy beneath them) except in general terms as part of broader texts. This prompted me to embark on my own investigation and research into the administrative working of the Raj using an analysis of the relationship between the Governors, Viceroy and the British Government and Parliament to do so. My core discoveries were quite interesting (See a Governors’ Raj, Macnamara, 2015). While ICS Governors of the provinces were never appointed as Presidency Governors or to the position of Viceroy it was in fact these men who provided the critical foundation for the efficient administration of British India. It was the Governors, drawing on their extensive broadly based knowledge of India and Indians gained during their careers who provided the necessary advice both political and administrative to the Viceroy during his tenure, particularly in its early stages. Given the Viceroy almost invariably had little to no knowledge of India before arrival he very quickly sought advice from the Governor cadre who were experts in their administrative and political knowledge of their provinces and in the context of nationalism. It was the Governors who could advise the Viceroy on the temperature of local nationalism and provide policy advice on how to meet it. It was they who actually knew the leading nationalists, their personalities and behaviours. It was they who understood the administrative requirements necessary for the efficient running of their provinces and of the whole of India. The Presidency Governors were to rely on their ICS cadre for their advice and support in a similar way.

I had chosen the period of Lord Irwin’s Viceroyalty from 1926 to 1931 to examine the nature of the governing and administrative relationship between the Viceroy, his Governors and the metropolis to gain a broader understanding of the governance of British India. This required research into the functioning of the eighteen Governors who served under Irwin during his tenure. All apart from the six Presidency Governors had long and distinguished careers in the ICS. These twelve had a deep knowledge and expertise in the functioning of their respective provinces and how to keep them running effectively. And thus, as an extension British India as a whole. Lord Irwin, while he had an advisory Council, personally drew extensively on the Governors’ more specific expertise to provide himself with the necessary background to function effectively. It was the Governors’ guidance he used to formulate policy advice to the British Government and thus to the British Parliament.

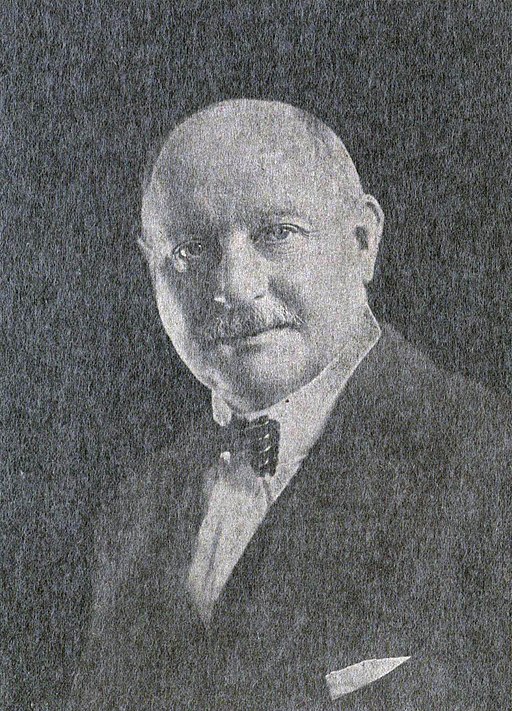

Of all the Governors who worked with Lord Irwin I found the most interesting of all to be Sir Spencer Harcourt Butler (who incidentally preferred to be addressed as Harcourt). Sir Harcourt was the most personable and he was clearly the most highly regarded rising through the ranks of the ICS very rapidly. Beginning his Indian career in the United Provinces in 1890 aged 21, he served as an Assistant Settlement Officer. Then followed progressive promotion to the positions of Joint Secretary to the Board of Revenue; Secretary to the Famine Commission; Director of Agriculture; Secretary of the Royal Commission upon Decentralisation. Following transfer to the central Government of India in Calcutta and Shimla, Butler became the second youngest person, at 39 ever appointed as Foreign Secretary to the Government of India. Then followed appointment as Education Member of the Viceroy’s Council. As effectively the Minister for Education he was extensively involved in education reform including the establishment of several Universities in India. In his position in the Government of India he was called upon for his ideas on the planning of New Delhi (he was the first President of the Imperial Delhi Gymkhana Club). Before his first appointment at the Gubernatorial level, he was appointed as Vice President of the Imperial Legislative Council. Then followed appointments as Lieutenant Governor of Burma then of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh and then later their full Governorships. Sir Harcourt was regarded so highly he was mooted by his contemporaries for appointment as Viceroy, which would have set an exceptional precedent. This was not to happen, but his vast experience and expertise was heavily drawn upon by the six Viceroys he served under ranging from Lord Curzon in the 19th Century to Lord Irwin in the 20th.

While Butler’s ICS career can be regarded as exceptional his pathway provides a clear guide to the role and functioning of the British Governors in the administration of British India. A study of his career illustrates the method and manner in which the British ruled India. Each of the positions he held provides the background to the actual administrative and policy process taken to achieve efficient government. His personal relationships with important Indian figures, including Princes, Talukdars and the Indian nationalists provide clear illustration of how the British used formal and informal contact to achieve outcomes.

An examination of Sir Harcourt’s record in India also gives the opportunity to explore the British attitude to the possibility of Indian Independence. A school of thought has it that the British did not wish to give up India, despite for example the introduction of legislation such as the Morley Minto Reforms, that could lead in that way. Butler was involved in policy advice (Butler’s advice was regarded at the time as liberal) leading to the reformist 1919 Government of India Act, which included provision for a review, every ten years of the ability of Indians to govern themselves. This review process has been pointed to as a means for the British to delay independence indefinitely. Political parties and persons in Britain sent different messages regarding their intentions for the future of India. Butler was at the heart of the policy making process which developed the British response to nationalism and attitude to future independence. His papers reveal the somewhat schizophrenic and confused position on this question the British held that permits a view that they were prevaricating. On the one hand Butler reveals he believes that India cannot do without the British and that he doesn’t believe in democracy and on the other he actively and enthusiastically implements democratic principles and practices in India and Burma, which must inevitably lead to independence. Further, he actively cultivated strong personal relationships with India’s ruling Princes and large landowners as supporters of British rule. Was it really nationalism and the economic pressures of two World Wars that forced the British to give up the Raj? Butler’s apparently confused approach personifies the overall contradictory nature of the British position on this question.

Sir Harcourt served in India for some 38 years. During this time, he was a contemporary and often a close friend, including of some Viceroys of many important historical figures. He met with British Kings, British and Indian Princes and Prime Ministers and worked with such famous men as Generals Kitchener and Birdwood. He developed personal relationships with leading Indian nationalists. His papers provide not only historical insights into these people and into the times in which they lived but also into how the British lived their personal lives in the Indian environment so remote from their home.

My research and work on Sir Harcourt Butler has led to the forthcoming publication, in the near future, by Peter Lang of my book: Sir Spencer Harcourt Butler: A Master Governor in British India: 1890-1928. Drawn from Butler’s extensive personal papers held in the British Library the book provides the condensed detail of his official and private life in some 300 pages (?). The publication allows a detailed exploration of the themes and questions raised above and as a research tool is an entry into Butler’s archive. It will be of interest not only to scholars but also to the general reader.

Image credit: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harcourt_Butler_(cropped).jpg