Behind American Prison Policy and Population Growth

An Inside Account

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the Book

- Advance Praise

- Dedication

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- 1 Correction Officer Basic Training

- 2 Getting Started at the Prison Colony

- 3 Inmate Housing Unit 1–2

- 4 The 4:00 by 12:00 Shift

- 5 The Quiet House

- 6 Lifers and Almost and Soon To Be

- 7 More Responsibility Through Experience

- 8 The Pre-Release Center by Fenway Park

- 9 Urban Pre-Release for a Short Time

- 10 Working with the Sick and Imprisoned

- 11 Bulletproofish

- 12 The People’s Republic of Boston Pre-Release

- 13 Opening a Treatment Center

- 14 Incarcerated Drunk Drivers

- 15 Finding My Way to the Training Academy

- 16 Basic Training and Beyond

- 17 Where to from Here

- Index

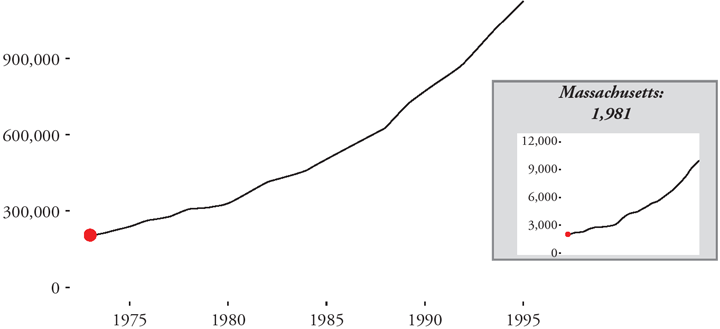

Figures

Figures

Figure 0.1United States prison population: 204,211

Figure 1.1United States prison population: 218,466 (+7% from 1973)

Figure 2.1United States prison population: 218,466 (+7% from 1973)

Figure 3.1United States prison population: 240,593 (+18% from 1973)

Figure 5.1United States prison population: 262,833 (+29% from 1973)

Figure 6.1United States prison population: 276,157 (+35% from 1973)

Figure 7.1United States prison population: 307,276 (+50% from 1973)

Figure 8.1United States prison population: 314,457 (+54% from 1973)

Figure 10.1United States prison population: 329,821 (+62% from 1973)

Figure 11.1United States prison population: 413,806 (+103% from 1973)

Figure 12.1United States prison population: 462,002 (+126% from 1973)

Figure 13.1United States prison population: 502,507 (+146% from 1973)

Figure 14.1United States prison population: 585,084 (+187% from 1973)

Figure 15.1United States prison population: 627,600 (+207% from 1973)

Figure 16.1United States prison population: 882,500 (+332% from 1973)

Figure 17.1United States prison population: 1,125,874 (+451% from 1973)

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This book has been a protracted process which involved many. I start with the workers and guests of the Massachusetts Department of Correction. Their stories tell the personal impact of a government policy based on inadequate reflection. Dante Germanotta and Peter Hainer, my social science professors at Curry College who urged me to journal my experience. Dina Booher, Eric Bronson, and Adam Braver for their encouragement. The succession of editors Jayne Irvine, Martha Sacks, Joanne Turnbull, Nathan Menton, James Brady, and especially Susan Solomon. Dianne Nerboso, Donna Cataldo, and others who took the time to read and provide feedback. Floyd Nelson at the American Correctional Association, whose faith in the work was fortifying. Michelle Smith at Peter Lang Publishers who moved on a belief in the value of the book. Most importantly, my partner Judy Menton who has been with me from the time I worked in corrections through the protracted process writing about that experience. Her edits, critiques, and tireless support of the venture enabled fruition. To all I am grateful.

Prologue

Prologue

1973

During the two years prior to the start of my employment in 1974, the state corrections system opened a pre-release center at the state hospital in Boston and acquired the former reform school which started out as a Shaker community and now was going to be a minimum-security corrections facility. A new state hospital for the criminally insane was also opened after years of controversy regarding the condition of the original facility built in the 1800s. Chamber pots were still in use when it was closed.

In January of 1995, I retired from the Massachusetts Department of Correction. In the twenty years I worked for the Mass DOC, the correctional population in the United States at least quadrupled. This historic expansion of imprisonment was caused by the redefining of criminality and the hardening of penalties. This is the story of what I saw and did while my workplace expanded and grew packed with criminalized people. This book tells the story of a career in the (Massachusetts) prison system. The correctional practices and developments in the field existing during that time are germane to the story. Therefore, some history, facts, and figures are offered at the start. This is the milieu that transforms over the course of the tale.

For decades before 1974, the year I began at the Norfolk Prison Colony, corrections had been a small operation run by various government entities: municipalities, county sheriffs, all the states, the federal government, and the military. They were small enterprises. The national average during the first three quarters of the 20th century was less than 1 in 1,000 people were in prison. Corrections were at that time a peripheral part of the government’s work. Prisons were located in out-of-the-way places or at least places out of the way when they were built.

In some cases the facilities could be over one hundred years old, or in the words of the corrections officer giving a tour of the New Bedford County jail, “parts of this facility were built during the administration of John Quincy Adams.”

These were forgotten places where harsh realities were mixed with instances of compassionate empathy in an environment dominated by boring routine. Placing penitentiaries in out-of-the-way locations was based on William Penn’s ‘Great Law’ (1682). He believed society had negatively influenced the offender and the solitude of prison would provide him/her with opportunities for reflection, prayer, and the resolve to become a better person.

Then came the tumultuous 1960s, a time of transition. The courageous civil rights protesters, their wretched treatment, and legal victories inspired others. The advances of civil rights workers served as instruction to other marginalized groups. Farmworkers, anti-war protesters, women’s liberation movements, and gay rights activists, as well as prisoner rights groups emerged with demands for fair treatment.

By the 1970s, the veil of disinterest that separated the prisons from the public was starting to fall. A succession of prison riots beginning in the early 1950s culminated with the bloodiest riot in US history: On September 9, 1971 the New York State Prison at Attica was taken over by inmates. Four days later State Troopers and National Guard troops violently retook the prison. In the process, 29 inmates and 10 prison staff taken hostages were killed. All the deaths were by gunshot. The inmates had no guns (Meents, 1971).

The Attica tragedy prompted discussions of prison reform among state legislatures and experts. Soon after the incident, the State of New York commissioned a study to determine effective correctional practices. In 1974, Douglas Lipton and Robert Martinson finished an exhaustive study of effective prison policy. “Nothing works” was the popular interpretation of their research, although the prison reform movement had taken root in many correction agencies at the same time. The search for effective correction approaches continues with successes as well as failures. The most notable successes are found in the work of cognitive behavioral theorists and practitioners. Structured programs that teach inmates pro-social ways of acting and thinking have shown positive results.

Reforms have also failed on a number of levels. “Get tough on crime” slogans have been operationalized. Pursuing practices shown to be ineffective but viscerally satisfying have yielded the largest failures. The once pervasive correctional boot camps still exist in small numbers in spite of research evidence of their ineffectiveness at lowering reoffending rates.

The unprecedented historic growth of correctional populations is an outcome of our failure to provide liberty and justice for all. There are numerous explanations as to what precipitated our leaders to prefer criminalizing and punishment. Generally, this posture is shorthanded into a “get tough on crime” approach. Bills on the floor of various legislative bodies become reformed sentencing laws, which reflect a hardening of our society’s heart. The fruit of these laws is increased costs for the taxpayer.

From the offender’s point of view, sentences are often disproportionately longer than their act warranted. This perception is echoed by criminologists (Clear, 2007). In the 1960s or 1970s, this would be an unfortunate circumstance applying to the few people incarcerated. Now we incarcerate nearly 1% of the population. When the menu of intermediate sanctions is included, around 6 million people are under the correction umbrella in the forms of parole, probation, court-ordered treatment programs, community service, and more. Some are very effective. Others pursue client failure as a measure of victory. The “get tough” posture has led to probation and parole departments where finding clients in violation is valued more than finding the effective mix of programs and supervision. The clients’ welfare and success are subordinated to the mantra of protecting the public, which in the long run protects no one.

Truth in sentencing, mandatory minimums, three strikes, sentencing guidelines mandating judges’ sanctions, elimination of indeterminate sentencing, and a range of “reforms” of a similar ilk have produced an incarceration binge. To deny thousands of citizens’ liberty, we have built hundreds of new prisons, increased the capacities of many old institutions and contracted private industry to provide incarceration services. These resources are developed with security levels higher than needed. That is the analysis of the objective point-based classification standard of the federal government and the analysis of experts.

This system, which is really not a system as much as an amalgam, is of questionable effectiveness. It could be more effective if it were smaller and attended to its original mission to help reform those who can be reformed, and to keep safe those who cannot.

It would be remiss to prologue without mentioning the most peculiar feature of the US sanctioning system. One demographic segment of our population is dramatically overrepresented in corrections. African American males make up 7% of the United States population and on average over 50% of the incarcerated population. Prison is an integrated part of society. Here, Black men make up a substantial percentage. This majority status impacts the hierarchy of the prison subculture. African American males have a litany of collateral negative impacts before they have any contact with the criminal justice system (NAACP, 2020). During this frenzy to imprison law breakers, a young Black man was more likely to be in prison than in college. The stigma of a criminal record and ex-inmate status exacerbates the social disadvantages already so common to men of color in America (Baum, 2016).

Working in prison is difficult, but working in prison is not as difficult as living there. Prisons are stratified societies dominated by a few predators. Overwhelmingly, incarcerated people in the US are men (92–95%) with a 9th-grade education who were high when they committed their crime (Williamson, 1992). Prisoners usually have spotty or non-existent work histories and come from low socio-economic classes.

In the latter part of the 20th century, deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals, state institutions for the developmentally disabled, took place in the hope that community placements would be more humane and to save states tremendous amounts of money (Miller, 1989). Currently the mentally ill and disabled are disproportionately represented in prisons and jails.

Details

- Pages

- XX, 226

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433179990

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433180002

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433180019

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433180026

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433188398

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17078

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (December)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. XX, 226 pp., 16 color ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG