Summary

Richard Hageman: From Holland to Hollywood is the first critical biography to reconstruct Hageman’s colorful life while recreating the cultural milieu in which he flourished: opera in America during the first half of the twentieth century and film scoring in Hollywood in the heyday of the studio system. Here Hageman’s most important works are analyzed in depth for the first time, from his famous art song, "Do Not Go, My Love" and his opera Caponsacchi, to his film scores such as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and 3 Godfathers. This biography offers a compelling read for opera lovers, film fans, and American history enthusiasts alike.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Note on Sources

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Great Expectations

- 2 The Metropolitan Years

- 3 Opera Conductor and Pioneer

- 4 The Caponsacchi Years

- 5 Destination Hollywood

- 6 Bicycling between Assignments

- 7 The War Years

- 8 Back on Top in Hollywood

- 9 3 Iconic Westerns

- 10 Twilight Years

- Conclusion

- List of Works

- Index

Illustrations

Illustration 1.1 Richard Hageman’s birthplace, Leeuwarden, the Netherlands 1906

Illustration 1.2 Richard Hageman and Rosina Van Dyck, New York 1909

Illustration 2.1 Francis MacMillen and Richard Hageman, circa 1907

Illustration 2.2 Rosina Van Dyck in Die Walküre, Metropolitan Opera 1909

Illustration 2.3 Sketch of Richard Hageman by Hy Mayer, New York 1909

Illustration 2.4 The Operatic Society Golf Tournament, Los Angeles 1926

Illustration 2.5 Richard Hageman with friends, Ravinia Festival 1917

Illustration 3.1 Richard Hageman and Renée Thornton, New York 1922

Illustration 4.1 Richard Hageman and the Tragödie in Arezzo production team, Freiburg, Germany 1932

Illustration 5.1 Richard and Eleanore Hageman at home, Beverly Hills 1937

Illustration 5.2 Richard and Eleanore Hageman entertaining, Beverly Hills 1938

Illustration 8.1 Richard Hageman with Louis Armstrong in New Orleans (1947)

←ix | x→Illustration 8.2 The émigré community at Alma Mahler’s 80th birthday, Beverly Hills 1948

Illustration 9.1 Richard Hageman in 3 Godfathers (1949)

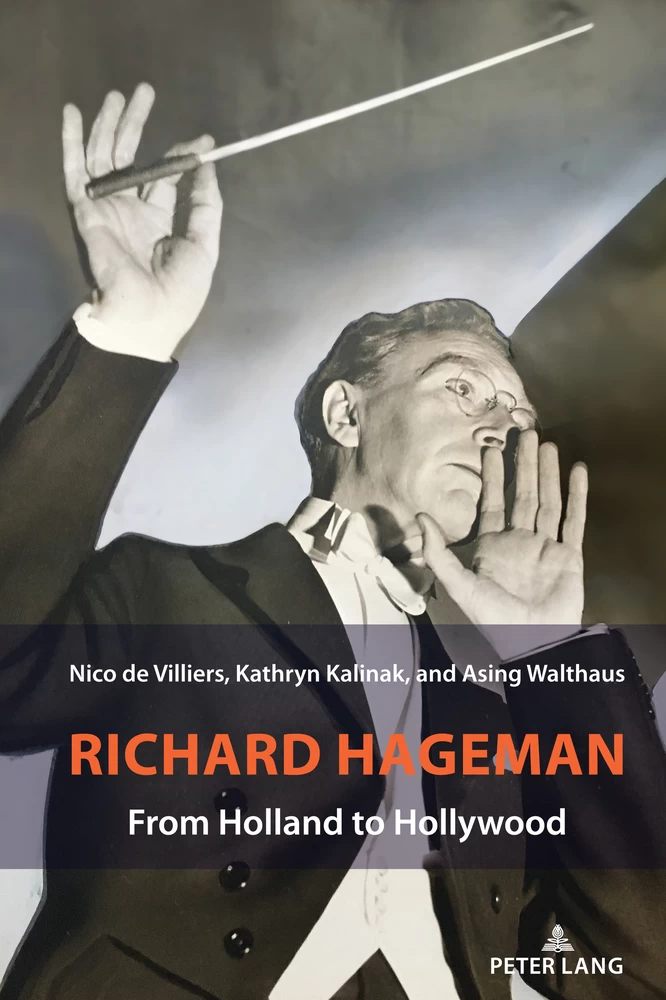

Illustration 10.1 Richard Hageman publicity photo, Hollywood 1940

Note on Sources

Frequently used newspapers, magazines, and journals are cited in the notes as follows: AH (Algemeen Handelsblad [General Trade Magazine], Amsterdam); AC (Atlanta Constitution); BDE (Brooklyn Daily Eagle); BG (Boston Globe); Caecilia (Caecilia: Algemeen muzikaal tijdschrift van Nederland [Caecilia, General Musical Magazine of the Netherlands], Amsterdam); CT (Chicago Tribune); DT (USC Daily Trojan); Telegraaf (De Telegraaf, Amsterdam); DS (Desert Sun, Palm Springs); DSP (De Sumatra Post); FD (Film Daily); HCN (Hollywood Citizen-News); HEN (Harrisburg Evening News); HR (Hollywood Reporter); LC (Leeuwarder Courant); LADN (Los Angeles Daily News); LAT (Los Angeles Times); MA (Musical America); MC (Musical Courier); MPD (Motion Picture Daily); MST (Minneapolis Star Tribune); NvdD (Nieuws van de Dag [News of the day], Amsterdam); NYDN (New York Daily News); NYHT (New York Herald Tribune); NYT (New York Times); NYTribune (New York Tribune); PCM (Pacific Coast Musician); PPG (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette); RN (Rotterdamsch Nieuwsblad [Rotterdam News Magazine]); SFE (San Francisco Examiner); Standard (The Standard, London); Variety (Daily and Weekly).

Frequently used databases are cited as follows: AHNAO (Ancestry Historical Newspaper Archive Online); ANNO (Historische österreichische Zeitungen und Zeitschriften [Historical Austrian Newspapers and Magazines]); CDNC (California Digital Newspaper Collection, University of California, Riverside); CHOA ←xi | xii→(Carnegie Hall Online Archive); DAHR (Discography of American Historical Recordings, UC Santa Barbara); Delpher (Delpher Digital Library, Koninklijke Bibliotheek [Royal Library], The Hague); EIMA (Entertainment Industry Magazine Archive); Gallica (Gallica Digital Library, Bibliothèque National de France [National Library of France], Paris); HT (HathiTrust Digital Library); JSTOR (JSTOR Online Library); Lantern (Lantern Digital Media History Project, University of Wisconsin, Madison); Met Online (Metropolitan Opera Archives Online); NAO (Newspaperarchive Online); NYTOA (New York Times Online Archive); Proquest (Proquest Historical Newspapers); Trojan (Daily Trojan Online Archive, USC).

Archives consulted are cited as follows: CI (Curtis Institute of Music, Philadelphia); Ford (John Ford Manuscript Collection, Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington); KH (Koninklijk Huisarchief [Archives of the Royal Family], The Hague); MHL (Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills); Met Archives (Metropolitan Opera Archives, New York City); Paramount (Paramount Pictures Music Department Records, Hollywood); PSA (Pittsburgh Symphony Archives); RHS (Richard Hageman Society Archives, London); WB (Warner Bros. Archive, USC).

Sources are cited in full at first mention; subsequent references are by author’s last name and shortened title (and page number if appropriate) unless the article is unsigned (as in newspaper articles) and then only the title is used. Newspaper articles without a headline are denoted by n.t. (no title).

Foreign names are cited in the text in the original language at first mention (Concertgebouworkest) followed by a translation if necessary (Concertgebouw Orchestra); subsequent references are to the English translation. Foreign titles in the Notes are cited in the same way but subsequent references are to the title in the original language.

All translations from the Dutch, German, and French are by Asing Walthaus.

Acknowledgements

Ours was a collaboration across three countries, three native languages, two continents, and three time zones. This shouldn’t have worked but somehow it did. Thanks here to the many people who helped us in our quest to find Richard Hageman.

Edward (Ned) Comstock, USC Cinema Television Library; Yuriy Shcherbin, USC Digital Library; Linda Showalter, Marietta College Legacy Library; and the staffs of Adams Library, Rhode Island College; Music Library, USC; Los Angeles Public Library, Pacific Palisades; Beverly Hills Public Library; Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Rosa Mason, Los Angeles Philharmonic Association; Carolyn Friedrich, Pittsburgh Symphony Archive; John Pennino, Metropolitan Opera Archive; Mark Duijnstee, Opera Nederland, Rotterdam; Rainer Schubert, Volksoper Wien [People’s Opera], Vienna; Katrin Böhnisch, Sächsische Stadttheater [Saxon City Theaters], Dresden; Frans Damman, Castrum Peregrini Foundation, Amsterdam; Lisa D. Roush, New Milford (Connecticut) Historical Society; Andrea Ladwig, Bundesarchiv [Federal Archive], Berlin; Gertrude Weel-De Raad, Koninklijk Huisarchief [Archives of the Royal Family], The Hague; Klaas Zandberg, Historisch Centrum Leeuwarden [Leeuwarden Historical Center]; and Paola Barzan, Università degli Studi di Padova. And Kathrin Korngold Hubbard, Elizabeth Renton Miller, Dan ←xiii | xiv→Ford, Stefanie Walzinger, Penny Johnson, Johann de Graaf, Caryl Flinn, Thomas Hampson, Kitty Chibnik, and the Faculty Research and Development Fund at Rhode Island College.

To our family, friends, and pets, thank you for your love and your support of our obsession with Richard Hageman.

And finally thanks to an anonymous usher at the Metropolitan Opera who, when asked if he knew where Richard Hageman’s photograph was, brought us directly to his portrait on the Met’s wall of performers and began singing, “Do Not Go, My Love.”

Introduction

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences held its awards ceremony for 1939 on the night of February 29, 1940. Typical of the Academy in this era, the ceremony was held at a hotel preceded by a dinner, this year at the Coconut Grove in the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. Bob Hope served as the emcee, the first of 18 times the actor would fill that role, raising it to iconic status. The festivities were supposed to begin at 10:00 pm but it was closer to 11:00 pm before Frank Capra, the Academy’s president, made his opening remarks. The night belonged to Gone with the Wind, David O. Selznick’s blockbuster adaptation of Margaret Mitchell’s Civil War novel, winning the top awards. The film’s charismatic star, Clark Gable, however, lost the Actor award to Robert Donat for Goodbye Mr. Chips and Max Steiner lost Original Score to Herbert Stothart for The Wizard of Oz. A bigger disappointment was the fact that the Los Angeles Times, given the winners’ names on condition that they remain secret, leaked the news in their evening edition at 8:45 pm. The next year the Academy instituted the practice of sealed envelopes for the winners.

The technical awards came first, not unlike today’s telecasts. There were three Music Awards—Song, Score, and Original Score.1 The Academy Award for Song went to Harold Arlen and E. Y. Harburg, for “Over the Rainbow.” The Score category was especially competitive with 12 nominations including two of the most celebrated composers in the studio system, Alfred Newman and Erich Wolfgang ←1 | 2→Korngold, as well as an acclaimed composer from the concert world, Aaron Copland. It must have been quite a surprise when four composers took the prize for Stagecoach (1939): Richard Hageman, Frank Harling, John Leipold, and Leo Shuken. Hageman did not come to the podium. He was in Pasadena, California, accompanying a young tenor, Arthur Renton, in his debut recital, a previous commitment Hageman chose to keep. Thus, there are no photos or film of Hageman receiving his award.

Hedda Hopper, the entertainment columnist for the Los Angeles Times, known as the gargoyle of gossip, got the scoop. “I believe in passing on the good with the bad, and here’s one of the sweetest stories I’ve heard in ages.”2 Hageman told Hopper that he was notified of his win the day before the ceremony.3 When the Academy made it clear that Hageman must attend in order to accept the award, he told them, “I’m sorry but I have promised a rising young tenor I’d play for him, and I wouldn’t let him down for all the Academy Awards in the world.”4 It was unheard of for winners to ignore the Academy much less forego the publicity generated by a win. Even Hopper was impressed.

Hageman was born in Leeuwarden in the Netherlands and raised in Amsterdam in Holland. He ended in Hollywood with an Oscar on his mantel. And in between he conducted operas and symphony orchestras, accompanied famed soloists, composed art songs and an opera, and taught a generation of singers and accompanists.

As a child, Hageman was a prodigy on the piano. As a young man he accompanied the famed French cabaret singer Yvette Guilbert on two concert tours of the United States. By 1908 he had secured an appointment as a conductor and coach at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, known as the Met, a post he held until 1921. For his debut, he conducted Enrico Caruso in Gounod’s Faust. He helped found opera companies in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Toronto, and was part of the faculty of the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. He was an acclaimed accompanist and vocal coach. He conducted symphony orchestras across the country and was a regular at the Hollywood Bowl, the large outdoor concert venue in the Hollywood Hills that is the summer home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He worked with some of the greatest soloists of the twentieth century: violinists Jascha Heifetz, Fritz Kreisler, and Efrem Zimbalist, cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, soprano Nellie Melba, and bass-baritone Paul Robeson. Hageman composed 69 art songs, many of which were regularly sung on concert stages during his lifetime. His opera Caponsacchi was broadcast live to the United States from Germany where it was described as “the most auspicious premiere of any American opera thus far offered in Europe”5; it was the first American opera ←2 | 3→to be produced in Vienna. Its U.S. premiere at the Met featured choreography by George Balanchine.

Like many a composer before him, Hageman found his way to Hollywood. There he would carve out a second career scoring pictures. He would score 16 films in all and receive six Academy Award nominations, winning for Stagecoach. Seven of his scores would be for the director of Stagecoach, John Ford, and five of them were for westerns, Ford’s signature genre. In the process, Hageman helped to define the sound of the American West. Hageman scored swashbucklers, war dramas, seafaring sagas, historical epics, and literary adaptations, too. He wrote the score for Paramount’s biggest-budgeted film of 1938, If I Were King, and he scored The Shanghai Gesture (1941) for Josef von Sternberg, one of cinema’s great stylists. Hageman was a sought-after guest at Hollywood parties where he would sit at the piano and entertain, often playing for the likes of Jeanette MacDonald, Nelson Eddy, Gladys Swarthout, and Lily Pons. During an acting career that flourished after the war, he was typically cast in roles that featured him playing the piano. Hageman jammed with Louis Armstrong in New Orleans (1947), accompanied Mario Lanza in The Great Caruso (1950), and played a saloon piano in a scene with John Wayne in 3 Godfathers (1948). And yet, in spite of a storied career that spanned the concert stage and the sound stage, Hageman is virtually unknown today, a footnote to music and film history in the twentieth century.

Hageman’s career was empowered and shaped by his European background and émigré status although he spent nearly his entire adult life in the United States. Hageman first emigrated in 1906 at a time in the musical life of the United States when artists with European credentials were thought superior to homegrown talent. As part of the first wave of European artists, Hageman came for the opportunities, economic and career-wise, that America offered. Within two years, he parlayed his experience as an opera conductor in the Netherlands into a contract at the Met. Seeking to establish itself as an opera house on a par with the reigning companies of Europe, the Met hired European personnel. Hageman benefited from this phenomenon not only at the Met but later in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Toronto where his status as a European combined with his talent opened doors for him. The same thing happened in Hollywood. In the 1930s, studios began actively courting composers with European credentials and experience in opera and the concert hall. Again, Hageman fit the bill. Hageman’s European background, however, provided not only traction for his career but friction as well. During World War I when Hageman was not yet a citizen, his European status made him suspect in some quarters and he found the need to defend himself as a loyal American in print. During World War II, Hageman, by then a ←3 | 4→longtime citizen, was protected against the discrimination European composers faced especially in Hollywood but he was singled out as European just the same.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 252

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433155826

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433155833

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433155840

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433155819

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433154737

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17449

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (January)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. XIV, 252 pp., 16 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG