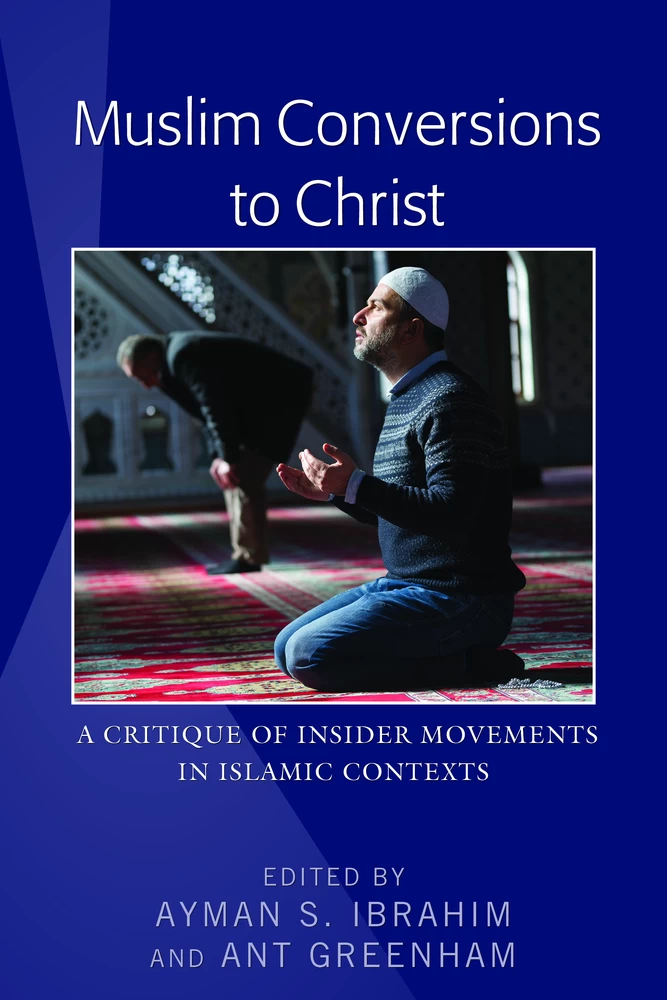

Muslim Conversions to Christ

A Critique of Insider Movements in Islamic Contexts

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- Advance Praise for Muslim Conversions to Christ

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword (R. Albert Mohler, Jr.)

- Preface (Ayman S. Ibrahim and Ant Greenham)

- Reference

- Part I

- 1. The Patriarch and the Insider Movement: Debating Timothy I, Muhammad, and the Qur’an (Brent Neely)

- Introduction: Muhammad and the “Insiders”

- Disagreeing with Both Vigor and Charity

- Part One: The Dialogue of Timothy I and the Caliph Al-Mahdi

- Timothy I on the Prophethood of Muhammad

- Timothy’s Context and Ours: Muhammad as a Prophet for Christians?

- Part Two: Talman’s Prophetic Continuum: Searching for a Taxonomy of Prophecy

- Types or Modes of Prophecy

- Problematizing Prophecy: Prophets and Their Character

- The Qur’an as Evidence of Muhammad’s Prophethood?

- Can We Jettison Islamic Tradition? Problems of Method

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Part II

- 2. Building a Missiological Foundation: Modality and Sodality (Bill Nikides)

- Backing into the Debate

- Defining Ecclesial Identity: Modality and Sodality

- Winter’s Two Structures

- Blincoe Furthers the Sodalist Cause

- Evaluating the Historicity of Modality and Sodality

- General Observations

- Evaluating Winter and Blincoe’s Historiography

- A Historical Coda

- Notes

- References

- 3. Why the Church Cannot Accept Muhammad as a Prophet (James Walker)

- Defining the Term “Prophet” with Respect to the Church

- Biblical Prophets and Biblical Criteria for Prophets

- Identification of the Real Muhammad

- Criteria for Identifying True and False Prophets: Message and Morality

- The Qur’an’s Actual Teachings on the Person of Christ and the Gospel Message

- Jesus’ Message Versus Muhammad’s Message

- IM Arguments and Objection to the Traditional Interpretation of the Qur’an’s Texts

- Talman’s Assumption That Muhammad Knew What He Was Talking About

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 4. Muslim Followers of Jesus, Muhammad and the Qur’an (Harley Talman)

- Preliminary Perspectives

- Insiders, Muhammad and the Qur’an

- Unpredictable Diversity at Multiple Levels

- Sundry Individual Insider Perspectives

- Observations from a Few Movements

- Response of Alongsiders to Muslim Insider Views of Muhammad and the Qur’an

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 5. Who Makes the Qur’an Valid and Valuable for Insiders? Critical Reflections on Harley Talman’s Views on the Qur’an (Ayman S. Ibrahim)

- Harley Talman, Insiders, and the Qur’an

- Redacting the Qur’an for Insiders’ Islam

- The Quranic Jesus Christ

- The Quranic Depiction of Christianity

- Divine or Literary Value of an Ancient Scripture?

- The Qur’an in Today’s Scholarship

- What if All Insiders Honor Muhammad and the Qur’an?

- Concluding Remarks

- Notes

- References

- Primary Islamic Sources

- Secondary Sources

- 6. Biblical Salvation in Islam? The Pitfalls of Using the Qur’an as a Bridge to the Gospel (Al Fadi)

- The So-Called CAMEL Method

- Allowing the Qur’an to “Take the Lead”

- Closer Examination

- The Challenge of Christian Hermeneutics of the Qur ’an

- Rejection of the Biblical Jesus

- Rejection of Core Christian Theology

- The Pitfalls of Quranic Comparisons

- The Dilemma of Quranic Revelation

- The Dilemma of Quranic Doctrines

- The Quranic Messiah

- Quranic Salvation

- Quranic Monotheism and Muhammad

- Quranic Abrogation

- The Dilemma of the Satanic Verses Incident

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 7. Insider Movements: Sociologically and Theologically Incoherent (Joshua Fletcher)

- Introduction

- Insider Movements: Definitions

- Isolating the Issues: The Dual Nature of Insider Identity

- Essentialism, Non-Essentialism, and the Problem of Defining Religion

- Religion: The Problem of Definition

- The Problem: Truncated View of Religion

- The Problem: Essentialism and Non-Essentialism

- Non-Essentialism: The Cultural View?

- Non-Essentialism and Defining Islam

- Insider Movement or Subversive Deconstruction?

- Necessary Criteria for Legitimate IM Dual Identity

- Insider Movements and Christian Theology

- The Confession: Beyond Proposition

- Judaism and the Confession

- Christianity and the Confession

- Islam and the Confession

- Conclusions: Non-Essentialism, Idolatry, and the Confession

- Jews and Gentiles, the Gospel and Conversion

- IM Claims Regarding the Gospel

- Scriptural Source and Nature of Second Temple Soteriology

- Structure of Second Temple Soteriology

- The Events of the Gospel

- The Spirit and His Relationship to Justification and Faith

- Paul’s Gospel: Redefining Election and Reorienting Praxis

- Conversion: Jews and Gentiles

- Conclusions Regarding Justification by Faith

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 8. The Biblical Basis for Insider Movements: Asking the Right Question, in the Right Way (Kevin Higgins)

- Background to the Issue

- Right Questions?

- Narrative One: 2 Kings 5

- Narrative Two: Acts 15

- Questions: Acts 15:1–5

- The Process: Acts 15:6–18

- The Conclusions: Acts 15:19–29

- Instruction: 1 Corinthians 8–10

- Conclusion: Are Insider Movements Biblical, and if So, in What Sense?

- Notes

- References

- 9. The New Testament Record: No Sign of Zeus Insiders, Artemis Insiders, or Unknown-God Insiders (Fred Farrokh)

- Introduction

- Defining “Insiders” and “Insider Movements”

- Insider Advocates’ Gentile Analogy

- Further Exegesis from Acts by Insider Advocates

- Disclaimer Regarding Messianic Judaism

- Examination of the New Testament Record

- The Gentile Religious Context

- The Pauline Mission to the Gentiles

- Acts Promotes Religious Discontinuity for New Gentile Believersin Jesus

- Application to Contemporary Ministry to Muslims

- The Covenant of Muhammad

- What Muslims Must Leave Behind to Experience New Life in Christ

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 10. Communal Solidarity versus Brotherhood in the New Testament (Ant Greenham)

- Communal Solidarity in the New Testament

- “Brothers” in the New Testament

- Purging the “Brotherhood”

- Jesus’ New Brotherhood

- The Vibrant Process of New Testament Conversion

- A Tragic Substitute

- Contemporary Applications

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 11. Messianic Judaism and Deliverance from the Two Covenants of Islam (Mark Durie)

- “Jew” and “Israel” Are Gospel Categories

- Messianic Judaism Has Profound Problems

- Lessons from Messianic Judaism for Insider Movements

- The Dhimma Covenant

- The Shahada Covenant

- Renouncing the Dhimma and Shahada Covenants

- Concluding Reflections

- Notes

- References

- 12. Word Games in Asia Minor (Duane Alexander Miller)

- Preface

- The Apostolic Practice and Insider Movements

- Antioch and the Pauline Churches

- The Early Church’s Mission to the Jews

- Christians in Turkey Today

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 13. “Son of God” in Muslim Idiom Translations of Scripture (Donald Lowe)

- Muslim Idiom Translations

- Discussion of Translating “Son of God” in Academic Journals

- Public Critique

- Wycliffe and SIL Responds

- The World Evangelical Alliance

- The Dust Settles

- Linguistics and Familial Terms

- Theology and Familial Terms

- Bible Translation, Discipleship and Churches

- Insider Movements and Muslim Idiom Translations

- Summary and Concluding Thoughts

- Notes

- References

- 14. Tawḥīd: Implications for Discipleship in the Muslim Context (Mike Kuhn)

- Introduction

- Survey of Islamic Tawḥīd

- Worldview and Mindset

- The Biblical Narrative and Worldview Formation

- The Biblical Narrative and Discipleship

- The Upper Room Discourse

- Old Testament Foreshadowing of the Trinity

- Tawḥīd and Trinity

- Culture and Understanding

- Implications and Current Reality

- Notes

- References

- 15. A Practical Look at Discipleship and the Qur’an (M. Barrett Fisher)

- The Good News of Jesus and the Qur’an

- The Good News of Jesus

- The Death and Divinity of Jesus According to the Qur’an

- Practical Implications for Discipleship

- Primary Focus on Jesus and the Gospel

- Avoid, Downplay or Address?

- Authority of the Qur’an?

- Never Appropriate to Slander the Qur’an

- The Qur’an as a Springboard

- Prepare Ahmad for Persecution

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Part III

- 16. Essential Inside Information on the Insider Movement (Paige Patterson)

- Defining the Insider Movement

- The Issue of Integrity

- The Great Commission

- Religious Syncretism and the Example of Jesus

- Truth Is Not Fuzzy

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 17. A Response to Insider Movement Methodology (M. David Sills)

- Reaching Muslims: Insider Movement (IM) Methodology

- Some Responses to These Arguments and Concerns

- An Invalid Comparison with Jewish Background Christians

- The Lordship of Christ

- The Importance of Careful Contextualization

- The good news

- The down side

- Islam’s Shame-Honor Context

- Christian Workers Are Not Muslims

- Jesus and the Church

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 18. Silver Bullets, Ducks, and the Gospel Ministry: Should We Seek One Best Solution for Winning People to Christ? (George H. Martin)

- Notes

- References

- 19. Radical Discipleship and Faithful Witness (Timothy K. Beougher)

- Note

- 20. Watching the Insider Movement Unfold (Georges Houssney)

- Eye Witness to the Movement’s Beginnings

- Development of the Insider Movement

- Three Stages of Development

- Explosion of Contextualization

- The Proliferation of the Movement

- Islamized Bible Translation Projects

- David Owen

- Sobhi Malek

- Mazhar Mallouhi

- Wycliffe Bible Translators

- Navigators

- Opposition to the Movement

- Hermeneutical Chaos

- When the Recipient Becomes Co-Author of the Message

- Handling the Word of God Correctly

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 21. The Great Commission and the Greatest Commandment (James Cha)

- Notes

- 22. Opening the Door: Moving from the Qur’an to New Testament Anointing (Don McCurry)

- Notes

- References

- 23. The Insider Movement: Is This What Christ Requires? (Carol B. Ghattas)

- What Do We Say About Muhammad?

- What Is My Religious Identity?

- What Is the Role of the Qur’an in the Life of the New Believer?

- Should the Language of the Bible Be Adapted for Those from Non-Christian Religions?

- What Is the Role of the Church?

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 24. Our Believing Community Is a Cultural Insider but Theological Outsider (CITO) (Abu Jaz)

- Cultural Insiders

- Theological Outsiders

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Reference

- 25. Question Marks on Contextualization! (Weam Iskander)

- Notes

- Reference

- 26. A BMB’s Identity Is in Christ, Not Islam (Ahmad Abdo)

- 27. Let Their Voice Be Heard (Azar Ajaj)

- Note

- 28. A Former Muslim Comments on the Insider Movement (Ali Boualou)

- Notes

- 29. The Insider Movement and Iranian Muslims (Mohammad Sanavi)

- Omitting or Changing the Titles “Son of God” and “Father”

- Use of the Word Allah in the Farsi Scriptures

- Use of Isa versus Yesu for Jesus in the Farsi Scriptures

- Use of the Qur’an in Evangelism

- The Crucifixion of Jesus

- The Deity of Jesus

- Is It Possible for a Person to Stay Muslim but Also Follow Jesus?

- Worshiping Alone in the Mosque versus Fellowship in the Church

- Sharing the Gospel in Another Culture

- Note

- 30. A Disturbing Field Report (Richard Morgan)

- An Overview of the Methodology

- A Case Where the Methodology Failed

- Suggested Explanations

- Note

- 31. The Insider Movement and Life in a Local Body of Believers: An Impossible Union from the Start (Daniel L. Akin)

- Notes

- References

- Epilogue: Force Majeure: Ethics and Encounters in an Era of Extreme Contextualization (David Harriman)

- Setting Out the Issue

- My Involvement with Frontiers

- An Ominous Letter

- An Investor’s Concern

- Becky Lewis’s Article

- Further Research

- Post-Resignation Developments

- Muslim-Idiom Translation (MIT)

- Communication with the “Smiths”

- A National Church’s Initiative

- Evaluating the Issues

- Implications of “Field-Led” Authority

- Maintaining a Fiction

- Frontiers’ “Recovery” of Biblical Missions

- World Evangelical Alliance Recommendations

- Concluding Observations

- Notes

- References

- Appendix: Do Muslim Idiom Translations Islamize the Bible? A Glimpse behind the Veil (Adam Simnowitz)

- Author’s Note

- Notes

- References

- Index

Ahmad Abdo is an Egyptian born again Christian from a Muslim background. He has been a believer from around 2010, and has been serving among Muslims in Egypt since his conversion. His ministry focuses on discipling Muslim converts in Egypt.

Abu Jaz (a pseudonym) is a believer and follower of the Lord Jesus Christ from a Muslim background. Since 2003 he has served the Lord in an East African country as Head of Christian-Muslim Relations in the Evangelical Churches Alliance. His activities include training and mobilizing evangelical churches, and church planting among Muslims. He also holds bachelor’s degrees in Bible and Theology, and in Global Studies and International Relations.

Azar Ajaj was born and raised in Nazareth, Israel, where he is an ordained minister, serving his Arab Israeli community in a number of ways over the past 25 years. He is a coauthor of Arab Evangelicals in Israel and is currently working on his Ph.D. degree with Spurgeon’s College, doing research on the history of the Baptists in Israel. He also serves as the President (and as a lecturer) at Nazareth Evangelical College.

Daniel L. Akin currently serves as President of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and is a Professor of Preaching and Theology. He and his wife Charlotte have been married since 1978 and have four sons, who all serve in the ministry. Together, they have traveled to countries in Africa, the Middle East, Central and South Asia, and South America, serving students and missionaries and helping share the gospel.

Al Fadi (a pseudonym) is a former Muslim from Saudi Arabia and follower of Christ. He is the founder and C.E.O. of CIRA International, a consulting agency focused on training and equipping (Christian) leaders in the field of Islamic Studies, through seminars, online Webinars and global media outreach, since 2002. He also hosts the popular radio show, “Let Us Reason—a Dialogue with Al Fadi.” ← xi | xii →

Timothy K. Beougher is Associate Dean of the Billy Graham School of Missions, Evangelism and Ministry at Southern Seminary, serving as Billy Graham Professor of Evangelism and Church Growth. Before coming to Southern Seminary in 1996, he taught evangelism at Wheaton College and was associate director of the Institute of Evangelism at the Billy Graham Center. He has authored numerous works on evangelism, discipleship, and spiritual awakening.

Ali Boualou, born and raised Muslim, converted to Christianity in 2002 in Morocco. He was ordained a pastor in 2007, serving a house church in Rabat, Morocco. He has led several Bible training courses among converted people in North Africa.

James Cha is a Presbyterian minister, conference speaker, writer and missionary in Washington, D.C., holding a B.S. and M.Eng. in Electrical Engineering, and an M.A. in Bible Exposition. While serving in Central Asia for ten years, he and his wife brought more than 120 Muslims to faith in Christ, and planted four house churches.

Mark Durie is an Anglican priest, evangelist and human rights activist, and Adjunct Research Fellow of the Arthur Jeffery Centre for the Study of Islam. He holds doctorates in linguistics (Australian National University) and quranic theology (Australian College of Theology), and pastors a congregation of former Muslims in Melbourne, Australia.

Fred Farrokh is a Muslim-background Christian. He holds an M.A. in Public Policy Analysis and Administration, and a Ph.D. in Intercultural Studies. He is an ordained missionary with Elim Fellowship, and has served with SAT-7 Middle East, Jesus for Muslims Network, and Global Initiative: Reaching Muslim Peoples.

M. Barrett Fisher has served in a Southeast Asia Muslim context for the past 10 years. He holds a B.S. in Business Administration, an M.Div. in Intercultural Church Planting, and a Ph.D. in Applied Theology.

Joshua Fletcher (a pseudonym) is an ordained minister with the Assemblies of God and serves with Assemblies of God World Missions in Central Eurasia. Focusing on discipleship and church planting among those from Muslim backgrounds, he speaks three non-Arabic languages. A graduate of the Brownsville Revival School of Ministry, he is close to completing a Master’s degree from Regents Theological College, focusing on the Spirit and justification by faith.

Carol B. Ghattas is a writer and speaker on Islam and ministry to Muslims. She earned her M.Div. from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary and served for over 20 years with her late husband, Raouf, as International Mission Board representatives in the Middle East and North Africa. Coauthor of their book A Christian Guide to the Qur’an, she continues to serve at the Arabic Baptist Church, which they founded, in Murfreesboro, TN. ← xii | xiii →

Ant Greenham is Associate Professor of Missions and Islamic Studies at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary. He earned his Ph.D. from Southeastern in 2004, with a dissertation on Palestinian Muslim conversions. Before embarking on his current academic career, he lived in the Middle East in a diplomatic capacity, opening the first South African Embassy in Amman, Jordan, in 1993.

David Harriman is a fundraising professional serving the Middle East region. Prior to five years in consulting with not-for-profit clients, he served for one year with Arab World Ministries, and for 18 years with Frontiers, principally as Chief Development Officer. Before joining Frontiers, he served with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship in development and missions, including as marketing director for the Urbana Student Missions Convention.

Kevin Higgins has served in the Muslim world in East Africa and South Asia. He was International Director of Global Teams from 2000 to 2017, and continues to serve as Muslim Ministries Coordinator for the Asia region, and oversees Global Teams’ growing involvement in Bible translation. He received a Ph.D. in translation from Fuller’s School of Intercultural Studies in 2013, and was appointed as the President of William Carey International University in 2017.

Georges Houssney, Lebanese born and raised, has been in full time ministry to Muslims and international students for over four decades. He holds degrees in Psychology, Education, and Linguistics. He is well known for directing a contemporary translation of the Bible into Arabic and is author of Engaging Islam. As founder and director of Horizons International, he travels extensively, preaching, teaching, training, and planting churches worldwide.

Ayman S. Ibrahim is Bill and Connie Jenkins Associate Professor of Islamic Studies at Southern Seminary, where he directs the Jenkins Center for the Christian Understanding of Islam. Born and raised in Egypt, he has authored The Stated Motivations for the Early Islamic Expansion. His articles on Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations appeared in The Washington Post and elsewhere. He is currently working on his second Ph.D. on Islamic History at Haifa University.

Weam Iskander is a Christian minister, writer, and leadership trainer in Egypt, holding a B.A. in Mass Communication, and an M.A. in Organizational Leadership. He has worked among believers in Christ in the broader Middle East and North Africa region for the past two decades.

Mike Kuhn has spent most of his adult life in Morocco, Egypt and Lebanon, serving in the areas of discipleship and teaching. Currently, he works with the Evangelical Presbyterian Church and is seconded to the Arab Baptist Theological Seminary in Beirut. He holds masters’ degrees in divinity and Arabic language and literature. His Ph.D. research was in the area of Arab Christian theological response in the Muslim context. ← xiii | xiv →

Donald Lowe is a church planter in Southeast Asia with World Team. He holds an M.S. in Electrical Engineering, an M.A. in Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary, and a Certificate in Applied Linguistics from the Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics.

George H. Martin is Professor of Christian Missions and World Religions at Southern Seminary, chairs the Department of Evangelism and Missions, and edits The Southern Baptist Journal of Missions and Evangelism. Before coming to Southern Seminary in 1996, he served in Southeast Asia and taught at North Greenville University.

Don McCurry, President of Ministries to Muslims, has worked in the Muslim world since 1957.

He holds a B.Sc. from the University of Maryland, an M.Th. from Pittsburg Seminary, an M.Ed. from Temple University, and a Doctorate in Intercultural Studies from Fuller Seminary. Currently, he teaches, mentors and coaches workers in many fields.

Duane Alexander Miller lives in Madrid, serving on the pastoral staff at the Anglican Cathedral of the Redeemer and adjunctively on the Protestant Faculty of Theology (U.E.B.E.). Author of Living among the Breakage: Contextual Theology-making and ex-Muslim Christians, with a Ph.D. from the University of Edinburgh on World Christianity, he is researcher/lecturer at-large in Muslim-Christian relations for the Christian Institute of Islamic Studies (San Antonio, Texas).

R. Albert Mohler Jr. is President of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. An authority on contemporary issues, he has been recognized by such influential publications as Time and Christianity Today as a leader among American evangelicals. In addition to his presidential duties, he hosts “The Briefing,” a daily analysis of news and events from a Christian worldview, and “Thinking in Public,” a series of conversations with the day’s leading thinkers.

Richard Morgan (a pseudonym) has been married 34 years, and is the father of two grown children. He worked in banking before serving as a pastor, and has over 12 years’ experience ministering among unreached peoples in Southeast Asia.

Brent Neely works with church-based outreach to refugees in Europe and humanitarian projects in the Middle East. He holds a Master of Divinity degree and is studying for the Ph.D. at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. He and his wife served in the Middle East for 18 years.

Bill Nikides is a Christian minister, writer and educator living in Italy. He holds a B.A. in History, two Masters degrees (to include an M.Div.), and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in theology. He has worked in the Muslim world for 39 years, 14 of which have involved church planting among Muslim convert Christians.

Paige Patterson serves as President of The Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas. He is also a Professor of Biblical Theology. Our ← xiv | xv → Lord has graciously allowed him to proclaim the good news of Christ in more than 130 countries.

Mohammad Sanavi was born into a devout Muslim family in Iran. During his last year of high school, he came to saving faith in Christ Jesus through the reading of a New Testament and the ministry of a Christian radio station. Over the subsequent 25 years, he has served among Iranian Muslims and Muslim converts to Christ. The author of several books and video resources, he provides theological education and training to Farsi-speaking pastors and church leaders.

M. David Sills is Founder and President of Reaching & Teaching International Ministries and A.P. & Faye Stone Professor of Christian Missions and Cultural Anthropology at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He holds an M.Div. from New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and a D.Miss. and Ph.D. in Intercultural Studies from Reformed Theological Seminary. He also served as a missionary in Ecuador.

Adam Simnowitz is a minister with the Assemblies of God. He holds a B.A. in Bible and Missions from Central Bible College (Springfield, MO), an M.A. in Muslim Studies from Columbia International University (Columbia, SC), and has studied Arabic in the Middle East. He and his family reside in Dearborn, MI.

Harley Talman (a pseudonym) is a missiologist, author, and professor with a Th.M. in Missions and Ph.D. in Intercultural Studies (in Islam). After two decades of church planting and theological education in the Middle East and North Africa region, he teaches Islamic studies and trains workers serving among Muslims.

James Walker has been engaged for over 25 years in Islamic ministry and research. He has led and taught numerous seminars for Christians interested in learning about Islam. He has also co-authored Understanding Islam and Christianity: Beliefs That Separate Us and How to Talk About Them with Josh WMcDowell.

Despite constant claims to the contrary, Christians and Muslims do not worship the same God. As Scripture makes clear on countless occasions no one can truly worship the Father while rejecting the Son. Jesus himself taught this very point when he told his opponents, “If you knew me, you would know my Father also” (John 8:19, ESV). Later in that same chapter, Jesus used some of the strongest language of his earthly ministry in stating clearly that to deny him is to deny the Father.

Christians worship the triune God, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and no other god. We know the Father through the Son, and it is solely through Christ’s atonement for sin that salvation has come. Salvation comes to those who confess with their lips that Jesus Christ is Lord and believe in their hearts that God has raised him from the dead (Romans 10:9). The New Testament leaves no margin for misunderstanding. To deny the Son is to deny the Father.

To affirm this truth is not to argue that non-Christians, our Muslim neighbors included, know nothing true about God or to deny that the three major monotheistic religions—Judaism, Christianity and Islam—share some major theological beliefs. All three religions affirm that there is only one God and that he has spoken to us by divine revelation. All three religions point to what each claims to be revealed scriptures. Historically, Jews and Christians and Muslims have affirmed many points of agreement on moral teachings. All three theological worldviews hold to a linear view of history, unlike many Asian worldviews that embrace a circular view of history.

Yet, when we look more closely, even these points of agreement begin to break down. Christian trinitarianism is rejected by both Islam and Judaism. Muslims deny that Jesus Christ is the incarnate and eternal Son of God and go further ← xvii | xviii → to deny that God has a son. Any reader of the New Testament knows that this was the major point of division between Christianity and Judaism. The central Christian claim that Jesus is Israel’s promised Messiah and the divine Son become flesh led to the separation of the church and the synagogue as is revealed in the Book of Acts.

There is historical truth in the claim of “three Abrahamic religions” because Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all look to Abraham as a principal figure and model of faith. But this historical truth is far surpassed in importance by the fact that Jesus explicitly denied that salvation comes merely by being one of “Abraham’s children” (John 8:39–59). He told the Jews who rejected him that their rejection revealed that they were not Abraham’s true sons and that they did not truly know God.

Now an even greater theological and missiological challenge has presented itself to the true church of the Lord Jesus, Insider Movements. Proponents of Insider Movements claim that a Muslim can truly repent of his or her sin and believe in Jesus as Lord and Savior while retaining “the socioreligious identity of his or her birth.” What is meant by that phrase? For many proponents of Insider Movements in a Muslim context, maintaining “socioreligious identity” includes continuing to affirm the Qur’an as Scripture, the prophethood of Muhammad, and even continuing to identify oneself as a Muslim.

Over and above claims that Christians and Muslims worship the same God, proponents of Insider Movements argue that a Muslim can become a Christian while still holding to most of his core theological convictions and even his religious traditions. But as explained above, the Bible is clear that one cannot follow Christ and continue to affirm the central theological convictions of Islam. Trinitarian orthodoxy and the doctrine of the incarnation counter every facet of Islamic theology. Christ’s claims on our lives demand separation from false convictions and corrupt religion. No person can truly follow after Christ and in any way affirm that Muhammad was a prophet or that the Qur’an is divinely inspired Scripture.

These are surely most pressing questions in the task of missions, particularly urgent in the encounter between Christianity and Islam. That is why I am enormously grateful for books like the one you are holding in your hand. Here Ayman S. Ibrahim and Ant Greenham have edited a collection of essays that addresses these questions with urgently needed and deeply thoughtful analysis. It is a timely, clear, compelling, and doctrinally sound volume that addresses Insider Movements within a Muslim context with grace, doctrinal precision, and missiological clarity. The editors’ theological analysis of these Movements is spot-on, and their biblical argument is utterly convincing.

Furthermore, the implications of this book go far beyond Christianity and Islam, reaching every aspect of our missionary task. Can one be both a Christian ← xviii | xix → and a Muslim? No. Ibrahim and Greenham make this case with both scholarship and passion. They want to see Muslims come to know Christ and be saved. They understand what is at stake. When you read this book, you will, too.

Hard times come with hard questions, and our cultural context exerts enormous pressure on Christians to affirm common ground at the expense of theological differences. But the cost of getting this question wrong is the loss of the gospel. Christians affirm the image of God in every single human being and we must obey Christ as we love all people everywhere as our neighbor. Yet love of neighbor also demands that we tell our neighbor the truth concerning Christ as the only way to truly know the Father.

AYMAN S. IBRAHIM AND ANT GREENHAM

This book was conceived in May 2015, when I (Ayman S. Ibrahim) received an email from a troubled Christian: “Is it really biblical to consider Muhammad a prophet? Have you seen the recent article on this argument by an Insider Movement’s advocate?” His troubled tone alerted me. He had been serving among Muslims for decades and actually witnessed dozens becoming followers of Christ, although he never accepted Muhammad’s prophethood, nor, a subsequent claim, that the Qur’an includes truth and light.

I was not aware of the article. It was only then that I was introduced to Harley Talman’s arguments and to Talman himself, as one of the top advocates of Insider Movements (IMs). When I read the article, I realized how Christians could (and should) be concerned about it, especially since the only published response it had received was somewhat positive—not engaging its potential theological and missiological perils. Consequently, I embarked on a written exchange with Talman, which was later published in three parts.

After completing my first response to Talman, I realized that the matter was so crucial it demanded far more than a simple exchange: The IM phenomenon involved a whole set of unhelpful claims, apparently stemming from Western attempts to enhance conversions (from Islam in particular), at the expense of basic biblical and theological orthodoxies. And in fact such claims were assembled in a later 2015 volume, co-edited by Talman, Understanding Insider Movements. That work includes various pre-published pieces, promoting an assemblage I have called “The Five Pillars of Insider Movements.”

The book you are now holding is a thorough response to that volume and to other IM assertions. My co-editor (Ant Greenham) and I asked scholars, pastors, believers from a Muslim background (BMBs), and missionaries to write fresh ← xxi | xxii → chapters for our volume. We chose them from the Arab World, Asia, Australia, Europe, and the United States. Their ranks include Anglicans, the Assemblies of God, Baptists, Presbyterians, and others.

A key concern underlying this multi-author response, is the conviction that Understanding Insider Movements fails to present the IM phenomenon adequately; in part because it omits important issues like biblical translations (at the authors’ own admission), in part because it uses pseudonyms without informing the reader, and in particular because it introduces IMs in a way that effectively ignores numerous, repeated, respected, evangelical voices expressing concern about such movements.

We acknowledge that IM proponents make important missiological arguments, to be judged on their merits. However, a critical issue is what they do not say. Selective use of the overall evidence, when that selection is slanted, can easily mislead those who lack the benefit of in-depth understanding of or exposure to IMs. This volume attempts to rectify that, even to the point of including chapters by two IM proponents, Talman and Kevin Higgins. In addition to including their perspectives (and offering rejoinders), this book features a wide array of other authors, noted above. Each one questions the IM phenomenon to a greater or lesser extent.

As might be expected, as editors, we do not agree with every sentiment these authors present (nor oppose everything in Talman and Higgins’s chapters). At some points our divergence is clear; at others it is left to the reader to trace the broad contours of this volume’s critique of IMs. We also recognize that this work is merely part of an important conversation, on what it means for Muslims, in particular, to become true believers in Jesus Christ.

Moving to the content of our volume, Part One comprises Brent Neely’s “The Patriarch and the Insider Movement: Debating Timothy I, Muhammad, and the Qur’an.” This magisterial yet irenic essay examines a historical case of Christian-Muslim interchange about Muhammad, and takes issue with the IM’s advocacy of a Christian embrace of Muhammad as a prophet on some level. It provides a remarkably thorough response to Harley Talman’s repeated attempts to “rehabilitate” the messenger of Islam.

Part Two consists of 14 substantial essays which address a range of biblical, theological, historical, and missiological issues. Bill Nikides begins with “Building a Missiological Foundation: Modality and Sodality.” He examines the origins and historicity of a parachurch-friendly paradigm, widely assumed to be valid by missionaries and organizations engaged in IM-type approaches, and shows that its claims to biblical and historical support are untenable. He is followed by James Walker’s “Why the Church Cannot Accept Muhammad as a Prophet.” This chapter argues stridently for the church’s traditional view of Muhammad as a false ← xxii | xxiii → prophet on the basis of biblical criteria for prophets, an identification of the real Muhammad, and the Qur’an’s teaching on Christ and the gospel.

In contrast to Walker, Harley Talman presents “Muslim Followers of Jesus, Muhammad and the Qur’an.” He condemns an “essentialist” approach to religion and argues that while insiders honor Muhammad and the Qur’an to a greater or lesser extent, their ultimate allegiance is to Jesus and the Bible. It is significant that Talman devotes considerable space in this chapter to what he sees as evangelicals’ mistaken essentialism when it comes to Islam. He does this before he answers the question put to him on how “Muslim followers of Jesus” see Muhammad and the Qur’an. He sees such essentialism as an assertion that Muslims hold “Muhammad and the Qur’an to be the final and greatest prophet and holy book.” Taking “essentialist” evangelicals to task on this, he throws down the gauntlet, arguing it is not necessarily the case: In fact, instead of getting worked up over the question of whether a Muslim follower of Jesus “honors Muhammad and the Qur’an or not,” we should rather seek “to understand what God is doing [in IMs] so that we can praise him.”

Ayman S. Ibrahim immediately takes up Talman’s gauntlet, in his “Who Makes the Qur’an Valid and Valuable for Insiders? Critical Reflections on Harley Talman’s Views on the Qur’an.” He laments Talman’s placement of praxis over Scripture (as he effectively encourages insiders to continue honoring the Qur’an), particularly in the light of what the Qur’an says about Christ and Christians. Al Fadi then follows hot on Ibrahim’s heels, with “Biblical Salvation in Islam? The Pitfalls of Using the Qur’an as a Bridge to the Gospel.” He points to the fallacy (and danger) of using the Qur’an as a witness to salvation in Christ (including the so-called CAMEL method). This approach not only affirms quranic authority and Islamic doctrines, albeit inadvertently. It also encourages quranic opposition to the biblical Christ and doctrine of salvation in the mind of a Muslim. The next chapter, “Insider Movements: Sociologically and Theologically Incoherent,” by Joshua Fletcher, shows that the sociological underpinnings for dual religious identity advocated by IM proponents are faulty. This is the case even on the basis of non-essentialism. In addition, Fletcher argues, Paul’s theology of justification (and conversion to a redefined Judaism) counters the IM argument that Muslims do not need to convert from Islam.

Next we move to Kevin Higgins, the other IM proponent to contribute to our volume. His irenic “The Biblical Basis for Insider Movements: Asking the Right Question, in the Right Way” reflects on the dispute over the biblical nature or otherwise of IMs. He seeks to refocus the questions by considering the accounts of Naaman (2 Kings 5), the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15), and Paul’s instructions on food offered to idols in 1 Cor 8–10. He also (understandably) laments the demonization he has experienced over the years, suggesting that advocates and opponents ← xxiii | xxiv → of IMs frequently talk past each other. He then asks whether we ask the right questions on the biblical or otherwise nature of IMs.

Fred Farrokh, a believer from a Muslim background, underlines the need to distance oneself from one’s birth religion in “The New Testament Record: No Sign of Zeus Insiders, Artemis Insiders, or Unknown-god Insiders.” He examines the biblical rationale for IMs and finds that Gentiles, though they did not need circumcision, experienced dramatic discontinuity from their pagan religious past. In the same way, Muslims must leave the covenant of Muhammad and his anti-biblical teachings on Jesus. In a similar vein, Ant Greenham’s “Communal Solidarity versus Brotherhood in the New Testament” demonstrates that use of the term brothers in the NT does not imply any kind of ongoing communal solidarity, not least in the light of the unity of Jesus’ radical new brotherhood, forged by true NT conversion to Christ. And that unity will also show itself in missions contexts today.

Mark Durie traces the history of so-called “Messianic Muslims” as analogous to Messianic Judaism in his “Messianic Judaism and Deliverance from the Two Covenants of Islam.” He argues that Messianic Judaism falters for submitting to the principles of Christ-opposing rabbinical Judaism. It is thus an unhelpful paradigm for discipling believers from a Muslim background (BMBs) who, along with the missionaries who serve them, must renounce both the servile surrender of Islam’s dhimma covenant and its Christ-denying Shahada. This is followed by Duane Alexander Miller’s interview-based “Word Games in Asia Minor.”

Responding to IM positions, he considers the nature of the church in Antioch in NT times and today. Quite simply, the Christian label was adopted to form one new distinct identity in apostolic times and beyond. Currently, very different Christian communities in the same location seek to incorporate new believers, changed from their Muslim identities, into the one Church established by Christ.

Donald Lowe moves in a somewhat different direction with “‘Son of God’ in Muslim Idiom Translations of Scripture.” He briefly describes the nature of Muslim Idiom Translations (MITs), traces the recent debate on use of the term “Son of God,” and considers familial terms in the Bible from linguistic and theological perspectives. He also stresses the importance of biblical discipleship as an aid to understanding Son of God language, and laments the lack of such discipleship by IM proponents. On the same subject, Mike Kuhn’s “Tawḥīd: Implications for Discipleship in the Muslim Context” demonstrates that discipleship drives the follower of Jesus towards a conception of God that diverges from the Islamic conception at critical points. While there are certainly commonalities between the Muslim and Christian conceptions of God, the biblical call of discipleship—which is active and intentional—will inevitably bring the distinctions into ever clearer focus. Ending Part Two, M. Barrett Fisher’s “A Practical Look at Discipleship and the Qur’an” asserts that missionaries should not hold a neutral to favorable view ← xxiv | xxv → of the Qur’an. It is Islam’s holy book which at the very least attributes no significance to Jesus’ death, and emphatically denies his divinity. The focus must always be on Jesus and his gospel as presented in the Bible.

Part Three consists of 16 short essays from a wide variety of contributors, including theologians, missiologists, missionaries, and practitioners. Paige Patterson begins with “Essential Inside Information on the Insider Movement.” Whereas much of the IM is based on accommodation and inadvertently on deceit, he asserts that our challenging call to missions must be answered with solid discipleship and unmitigated integrity. For his part, M. David Sills offers “A Response to Insider Movement Methodology.” He argues that missions methodology must be driven by sound philosophy, focused on Jesus’ lordship. Teaching Jesus plus anything else at all, is heresy. George H. Martin follows with “Silver Bullets, Ducks, and the Gospel Ministry: Should We Seek One Best Solution for Winning People to Christ?” He notes that we must not allow our passion for lost people to cloud our thinking—especially not to the point that an individual receiving the gospel could be encouraged to remain within, and continue to practice, the traditions of a religion clearly contrary to biblical Christianity. Then, Timothy K. Beougher presents “Radical Discipleship and Faithful Witness.” In line with Jesus’ words, a believer must break with the past, an approach which flows from integrity in witness.

Georges Houssney follows with a first-person account, “Watching the Insider Movement Unfold.” As he points out, the IM may be traced historically via the culture-accommodating approaches of indigenization and contextualization, leading to an encouragement to converts to remain within their religious contexts and the production of MITs for such contexts. Next, in contrast to the dangers Houssney identifies, James Cha highlights “The Great Commission and the Greatest Commandment.” Following the principle that the Greatest Commandment must drive the Great Commission, Cha relates the insistence in his former ministry in Central Asia that BMBs make a clean break with the Qur’an.

Continuing in the area of practical ministry, Don McCurry presents “Opening the Door: Moving from the Qur’an to New Testament Anointing.” He argues that the word “Christian” can be used as a practical door-opener to explain anointing by the Holy Spirit to Muslims, as one is reconciled to God through faith in Christ. For her part, Carol B. Ghattas offers “The Insider Movement: Is This What Christ Requires?” Reflecting on decades of ministry experience and on contemporary realities in the world of Islam, she indicates that BMBs turn to the biblical Christ and Christian faith even though they become outsiders in the process.

She is followed by an array of writers, some of them BMBs, operating largely in Muslim-majority countries. Abu Jaz presents a piece entitled “Our Believing Community is a Cultural Insider but Theological Outsider (CITO).” Whereas their culture connects them with the Muslim community, he points out that this ← xxv | xxvi → believing community in Africa acknowledges neither Muhammad as a prophet of God nor the Qur’an as the Word of God. Weam Iskander then expresses his concern in “Question Marks on Contextualization!” He argues that the IM (and its “extreme contextualization”) seeks to eliminate the challenges BMBs and Christian workers face in the Muslim world, not to speak of compromising core Christian beliefs surrounding Christ’s deity. Ahmad Abdo concurs in his first-person “A BMB’s Identity is in Christ, not Islam.” He explains that the IM complicates BMBs’ identity crisis. BMBs must be uprooted from Islam, not discipled by that which enslaved them.

Azar Ajaj adds his contribution in “Let Their Voice Be Heard.” BMBs in the Holy Land take the gospel seriously and, as he points out, wish to live out their faith in Christ without insider advocates’ impositions. In “A Former Muslim Comments on the Insider Movement,” Ali Boualou, a North African believer from a Muslim background, then argues that IM people are preaching a strategy that is virtually impossible to demonstrate, biblically wrong, ethically unacceptable, and shows no respect for Muslim friends and family. Mohammad Sanavi follows with “The Insider Movement and Iranian Muslims.” He asserts that biblical terms for God are essential to orthodoxy. The Qur’an cannot prove the Jesus of Christianity, since it rejects his crucifixion and deity. Moreover, encouraging vulnerable new believers to remain Muslim will destroy small but growing groups of BMBs in the Middle East.

Backing up these voices, Richard Morgan presents “A Disturbing Field Report.” In a context where Muslim terms for Jesus are used and multiplication is emphasized, a group of almost 1,000 “believers” fell back into sin and by 2016 had disappeared entirely. This unfortunate development leads Daniel L. Akin to conclude Part Three with “The Insider Movement and Life in a Local Body of Believers: An Impossible Union from the Start.” In the light of Jesus’ sacrifice for us, our most basic, reasonable commitment to him requires an embrace of NT patterns of witness and discipleship. Quite simply, discipleship is doomed in the absence of a gathered church.

After presenting a range of voices questioning Insider Movements and Muslim-Idiom Translations, we are pleased to offer David Harriman’s first-person account as an epilogue. In “Force Majeure: Ethics and Encounters in an Era of Extreme Contextualization,” Harriman recounts his experiences and reflections during and following 18 years of service with Frontiers, principally as Chief Development Officer. He details how without their knowledge, donors to Frontiers funded an Arabic translation of the Gospels and Acts that made significant changes to the language of Scripture. When a similarly-changed Turkish translation of Matthew was produced by Frontiers over the appeals and objections of the Alliance of Protestant Churches of Turkey (an association of Muslim-convert ← xxvi | xxvii → churches), the Alliance felt compelled to warn Turkish churches about the translation. Harriman argues that Frontiers appears to understand Islam in a way that Arab, Turkish, and other former Muslims do not, and sees a redemptive potential inherent within Islam, even if national Christians and former Muslims are blind to it. They believe they are “recovering” the contextual approach of Jesus Christ and the Apostles. Because existing translations of the Bible in Arabic, Turkish, and other languages are inadequate for their missional purpose, Frontiers believes they must translate the Bible for those who by apostolic command must remain Muslim—not simply culturally, but in terms of religious expression or identity.

Finally, we feature an appendix, “Do Muslim Idiom Translations Islamize the Bible? A Glimpse behind the Veil,” by Adam Simnowitz. Drawing on some of his previously published writings, including his thesis, Simnowitz’s appendix supports Donald Lowe’s essay in Part Two and provides examples of translations (in different languages spoken by Muslims) of ten specific texts of Scripture. As he notes, at best, the MIT phenomenon obscures the gospel of Christ. At worst, it deprives its intended Muslim audience of the message of salvation from sin and reconciliation with the triune Creator whose name is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

So, the stage is set for ongoing conversation on these important matters. It is our contention that IM proponents, for all their missiological acumen, risk abandoning the gospel, particularly in Muslim contexts. Whether we have made this case though, we leave to our readers to judge.

Reference

Talman, Harley, and John Jay Travis, eds. Understanding Insider Movements: Disciples of Jesus within Diverse Religious Communities. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2015.

Details

- Pages

- XXX, 532

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433154300

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433154317

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433154324

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433154331

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14187

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (May)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Vienna, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XXX, 532 pp., 2 b/w ill., 10 tbl.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG