European Football During the Second World War

Training and Entertainment, Ideology and Propaganda

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Figures

- Introduction Football: A Myth Machine. The Second World War, National Socialism and Anti-fascism (Markwart Herzog)

- Part I Greater German Reich

- 1 The German National Team: From the Last International Match During the War in 1942 to the First Postwar International Match in 1950 (Ulrich Matheja)

- 2 Viennese Football Players and the German Wehrmacht: Between ‘Duty’ and Evasion (David Forster / Georg Spitaler)

- 3 Football in Graz during the Second World War: The Traditional Clubs SK Sturm and GAK from 1939 to 1945 (Walter M. Iber / Harald Knoll)

- Part II Allied and Neutral Countries

- 4 Between Political Instrumentalization and Escapism: Spanish Football during the Second World War (Jürg Ackermann)

- 5 Football in Rome during the German and Anglo-American Occupation (1943–1945) (Marco Impiglia)

- 6 Neutrality as the Norm? Football and Politics in Switzerland during the First and Second World Wars (Christian Koller)

- 7 Switzerland’s International Matches during the Second World War: Sport and Politics, Continuities and Traditions (Grégory Quin and Philippe Vonnard)

- Part III Great Britain and Mandated Territories

- 8 War Heroes or ‘D-Day Dodgers’? English ‘Wartime Football’ (Fabian Brändle)

- 9 Bombs on Seats: Football and the Consequences of War in an English City (Gary Armstrong / Matthew Bell)

- 10 Football in the British Mandate for Palestine during the Second World War (Manfred Lämmer and Haim Kaufmann)

- Part IV Eastern European Countries

- 11 Football in the Occupied Soviet Territories: Leisure and Entertainment, Sport and Health, Politics and Ideology (Alexander Friedman)

- 12 Football during the Nazi Occupation of Kiev: A Contribution to the History and the Historical Context of the So-Called Death Match in Kiev (Maryna Krugliak and Oleksandr Krugliak)

- 13 Football in Occupied Zhytomyr (1941–1943): An Oasis of Normality amid War, Occupation and Genocide (Victor Yakovenko)

- 14 Football in Occupied Serbia (1941–1944) (Dejan Zec)

- 15 Football ‘Only for Germans’, in the Underground and in Auschwitz: Championships in Occupied Poland (Thomas Urban)

- Part V Football during the War as a Subject of the Arts

- 16 Football on the Front Line: The Silver Tassie, an Opera by Mark-Anthony Turnage (Martin Hoffmann)

- 17 Football as Politically Neutral Entertainment during the Nazi War: Content and Impact of Robert Adolf Stemmle’s Romantic Football Movie Das große Spiel (Markwart Herzog)

- 18 The Kiev Death Match: A Myth and Its Various Manifestations in Cinematic and Literary Works (Jan Tilman Schwab)

- Abbreviations and Short Terms

- Authors and Editors

- Index

- Series Index

European Football During

the Second World War

Training and Entertainment,

Ideology and Propaganda

Markwart Herzog and

Fabian Brändle (eds)

Translated by Karina Berger

PETER LANG

Oxford • Bern • Berlin • Bruxelles • Frankfurt am Main • New York • Wien

Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek

Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on

the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de?.

British Library and Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data:

A catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library,

Great Britain, and from The Library of Congress, USA

The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association)

Translation from Europäischer Fußball im Zweiten Weltkrieg

by Markwart Herzog and Fabian Brändle

© 2015 W. Kohlhammer GmbH, Stuttgart.

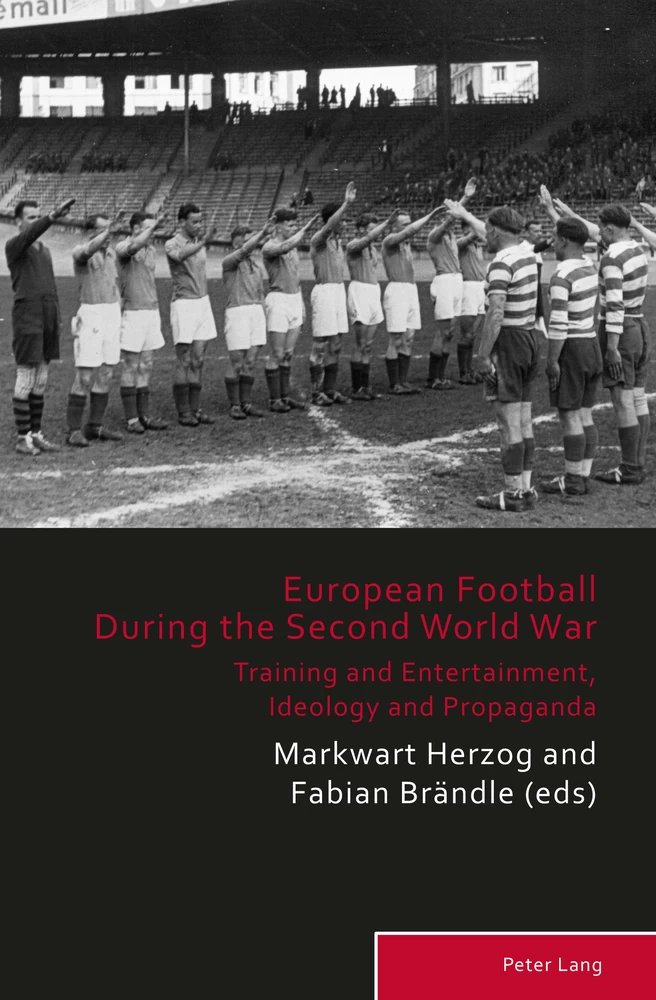

Cover image: Ritual of welcoming two German soldier football teams before the final match of the Military Football Championship of ‘Greater Paris’ 1942, Princes’ Park Stadium (Stade Vélodrome du Parc des Princes), Paris Saint-Germain, photograph provided by † Georg Lichtenstern, Pöcking.

|

issn isbn 978-1-78874-474-4 (print) isbn 978-1-78874-476-8 (eBook) |

isbn 978-1-78874-475-1 (ePDF) isbn 978-1-78874-477-5 (MOBI) |

Published by Peter Lang Ltd, International Academic Publishers,

52 St Giles, Oxford, OX1 3LU, United Kingdom

oxford@peterlang.com, www.peterlang.com

All rights reserved.

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright.

Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without

the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution.

This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming,

and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Markwart Herzog PhD is a philosopher of religion and sports historian and director of the Schwabenakademie Irsee. He works on topics related to the history of religion and history of sport. His main research interests include the cultural history of football, the commemorative and funerary culture of club football, the history of women’s football, sport in the National Socialist period and the media history of sport. He is a member of the International Society of Olympic Historians (ISHO), International Society for the History of Physical Education and Sport (ISHPES), Rotary Club Kaufbeuren, Deutsche Akademie für Fußballkultur and 1. FC Kaiserslautern.

Fabian Brändle PhDis a historian and author with a research focus on ‘history from below’, the history of folk and mass culture, the history of poverty, the history of childhood and youth, the history of the two world wars, Alsace, Tyrol and Ireland as well as the social and cultural history of sport, football and ice hockey in Switzerland.

About the book

When German troops marched into Poland on 1 September 1939, this also affected sport – sometimes dramatically. Official propaganda no longer viewed football as a game that was played for fun, but one that could be instrumentalized for political goals and military strategy. Due to the unpredictability of the game, football did not appear to be well suited to such a purpose. However, as the sport was able to create a politically neutral space that offered exciting entertainment and an escapist distraction, it was eminently important for the dictatorship. Soldiers and the civilian population benefited from this, as did the National Socialist regime itself. Football was vital for the war effort and also helped to stablilize the system precisely because it was not a vehicle for political propaganda. In this edited volume, an international team of authors examines the development of football during the Second World War in a dozen European states. The volume concludes with essays on the representation of the topic in the arts and the media.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Contents

Introduction

Football: A Myth Machine. The Second World War, National Socialism and Anti-fascism

1 The German National Team: From the Last International Match During the War in 1942 to the First Postwar International Match in 1950

David Forster and Georg Spitaler

2 Viennese Football Players and the German Wehrmacht: Between ‘Duty’ and Evasion

Walter M. Iber and Harald Knoll

3 Football in Graz during the Second World War: The Traditional Clubs SK Sturm and GAK from 1939 to 1945

Part II Allied and Neutral Countries

4 Between Political Instrumentalization and Escapism: Spanish Football during the Second World War←v | vi→

5 Football in Rome during the German and Anglo-American Occupation (1943–1945)

6 Neutrality as the Norm? Football and Politics in Switzerland during the First and Second World Wars

Grégory Quin and Philippe Vonnard

7 Switzerland’s International Matches during the Second World War: Sport and Politics, Continuities and Traditions

Part III Great Britain and Mandated Territories

8 War Heroes or ‘D-Day Dodgers’? English ‘Wartime Football’

Gary Armstrong and Matthew Bell

9 Bombs on Seats: Football and the Consequences of War in an English City

Manfred Lämmer and Haim Kaufmann

10 Football in the British Mandate for Palestine during the Second World War

Part IV Eastern European Countries

11 Football in the Occupied Soviet Territories: Leisure and Entertainment, Sport and Health, Politics and Ideology←vi | vii→

Maryna Krugliak and Oleksandr Krugliak

12 Football during the Nazi Occupation of Kiev: A Contribution to the History and the Historical Context of the So-Called Death Match in Kiev

13 Football in Occupied Zhytomyr (1941–1943): An Oasis of Normality amid War, Occupation and Genocide

14 Football in Occupied Serbia (1941–1944)

15 Football ‘Only for Germans’, in the Underground and in Auschwitz: Championships in Occupied Poland

Part V Football during the War as a Subject of the Arts

16 Football on the Front Line: The Silver Tassie, an Opera by Mark-Anthony Turnage

17 Football as Politically Neutral Entertainment during the Nazi War: Content and Impact of Robert Adolf Stemmle’s Romantic Football Movie Das große Spiel

18 The Kiev Death Match: A Myth and Its Various Manifestations in Cinematic and Literary Works←vii | viii→

Index←viii | ix→

Matheja

Figure 1.1: Results table in Fußball – Illustrierte Sportzeitung, 29 August 1939. (Archive Der Kicker/kicker-sportmagazin)

Figure 1.2: Reichssportführer Hans von Tschammer und Osten (right) presents player Franz Schmeiser of TSV München 1860 with the Tschammer-Pokal (today DFB-Pokal). 1860 had won the German cup a week before the game in Bratislava after a 2–0 victory against FC Schalke 04. Photo in: Der Kicker, 24 November 1942. (Archive Der Kicker/kicker-sportmagazin)

Figure 1.3: Headline in Der Kicker, 12 January 1943. (Archive Der Kicker/kicker-sportmagazin)

Figure 1.4: Forward Josef Gauchel of TuS Neuendorf (today TuS Koblenz), who scored thirteen goals in sixteen international matches between 1936 and 1942. Photo in: Der Kicker, 6 February 1943. (Archive Der Kicker/kicker-sportmagazin)

Figure 1.5: List of names of the 169 players appointed by Herberger during the war – both national and younger up-and-coming players. In: Joint war edition of Der Kicker-Fußball (last edition), 26 September 1944. (Archive Der Kicker/kicker-sportmagazin)←ix | x→

Figure 1.6: Poster for the first postwar international match on 22 November 1950 in Stuttgart against Switzerland. (Festschrift 100 Jahre DFB, p. 42)

Figure 1.7: The first postwar German national team. From left: Jakob Streitle, Fritz Balogh, Karl Barufka, Richard Herrmann, Gunther Baumann, Max Morlock, Bernhard Klodt, Ottmar Walter, Herbert Burdenski, Toni Turek, Andreas Kupfer. Photo in: kicker-sportmagazin, 22 November 2010. (photo Schirner)

Iber and Knoll

Figure 3.1: Sturm at the game against 1. FC Nürnberg, August 1940. (Hans Schabus, Graz)

Figure 3.2: Sturm and GAK’s rankings from 1934 compared to sports club Südbahn (Reichsbahn Sportgemeinschaft from 1938). (Harald Knoll, Graz)

Figure 3.3: SK Sturm’s Hitler Youth team, around 1939. (SK Sturm, archive)

Figure 3.4: Sturm team 1930–31; standing on far right, Josef Plendner. (SK Sturm, archive)

Figure 3.5: GAK team 1938–39; standing on far right, sports manager Karl Fiedler. (Dr Günter Fiedler, Graz)

Impiglia

Figure 5.1: Campionato Romano: Fulvio Bernardini, captain (number 9, Mater), puts pressure on the goalkeeper of Vigili del Fuoco during a match at the Velodrom Appio on 22 January 1944. (Marco Impiglia, archive)←x | xi→

Figure 5.2: AS Roma striker Amedeo Amadei in front of the family business, which was reopened in the autumn of 1944 after it had been destroyed by American air raids. (Marco Impiglia, archive)

Figure 5.3: Spectators in the PNF stadium during the deciding match AS Roma vs AC Fiorentina for the championship title on 4 October 1942. (Marco Impiglia, archive)

Figure 5.4: Referee Generoso Dattilo at a match during the 1942–43 championship. Dattilo had enjoyed running a ‘palletta’ tournament in the courtyard of a rectory in the Testaccio neighbourhood during the German occupation of Rome, where they used balls the size of a grapefruit, as well as goals that were about three metres wide and two metres high. (Marco Impiglia, archive)

Figure 5.5: AS Roma, travelling to a game in Campo del Vomero in Naples on 3 September 1944; standing on the far left, Bernardini; standing second right, Amadei. (Marco Impiglia, archive)

Figure 5.6a: Fulvio Bernadini’s letter to the secretary of FIFA, Ivo Schricker, 4 September 1944. (FIFA archive, Zurich: correspondence Italy – FIFA)

Figure 5.6b: Fulvio Bernadini’s letter to the secretary of FIFA, Ivo Schricker, 5 September 1944. (FIFA archive, Zurich: correspondence Italy – FIFA)

Figure 5.7: Brochure which the Sicilian journalist Tarcisio Del Riccio published on behalf of Eugenio Danese, the director of Corriere dello Sport in 1945; it kept fans in the south up to date with all the results of the championship in the north. (Marco Impiglia, archive)←xi | xii→

Figure 5.8: The former Piedmontese partisan ‘Nasone’ [big nose] with Juventus players during a practise break near Turin on 10 September 1945. From left: ‘Nasone’, Pietro Rava, Alfredo Foni and Felice Borel. (Marco Impiglia, archive)

Koller

Figure 6.1: Football soldiers. Most of the players wore their uniform in the first international match against Italy on 12 November 1939. (Swiss Football Association, archive)

Figure 6.2: General Henri Guisan, Commander-in-Chief of the Swiss army, welcomes national players Severino Minelli and Alfred Bickel before the international match against Italy on 12 November 1939. (Swiss Football Association, archive)

Figure 6.3: Keeping up morale. Civilians and soldiers at the international match against Hungary in Zurich on 16 November 1941. (Swiss Football Association, archive)

Figure 6.4: On 18 October 1942 Switzerland played ‘Greater Germany’ for the last time in Bern and suffered their 100th international match defeat. (Swiss Football Association, archive)

Figure 6.5: Neutral states among themselves: penalty box scene during the Switzerland vs. Sweden match on 15 November 1942. (Swiss Football Association, archive)

Krugliak and Krugliak

Figure 12.1: Poster for Starts’ first match against a German Flakelf on 6 August 1942.

Figure 12.2: Poster for the second leg of Start vs Flakelf, the so-called Death Match, on 9 August 1942.←xii | xiii→

Figure 12.3: Photo of the teams taking part in the so-called Death Match.

Figure 12.4: Poster for Start’s last game on 16 August 1942; Rukh were the opponents.

Figure 12.5: A monument commemorating the victims of the Death Match in front of the Dynamo stadium, created by sculptor Ivan Horovy and architects Voldemar Bogdanovsky and Igor Maslenkov in 1971. (Jan Tilman Schwab, Kiel)

Figure 12.6: Memorial by sculptor Anatoly Kharechko and architect Anatoly Ignashchenko at the Zenit stadium, the venue of the Death Match (now Start stadium), which was put up in 1981. (Jan Tilman Schwab, Kiel)

Figure 12.7: Memorial by sculptor Yuri Bakhalyka and architect Ruslan Kucharenko, which has been on Akademika Hrekova Street since 1999. (Jan Tilman Schwab, Kiel)

Zec

Figure 14.1: Report by Sport Club Yugoslavia on the destruction caused by the war, May 1941. (Archives of Serbia, Belgrade, Ministry of Education (G-3))

Figure 14.2: Document about the licensing of the Belgrade Regional Football Association in 1943. (Archives of Serbia, Belgrade, Ministry of Education (G-3))

Figure 14.3: Rajko Mitić, one of the best players in the history of Yugoslav football, who began his career in Beogradski Sport Club during the Second World War. (Novo vreme)

Figure 14.4: Caricature from 1943 about the passionate rivalry between Sport Club 1913 (formerly Sport Club Jugoslavija) and Beogradski Sport Club. (Ljubomir←xiii | xiv→ Vukadinović, Večiti rivali, Belgrad: Knjižara Ivan Gundulić, 1943)

Urban

Figure 15.1: Photo of a league match between Polonia Warsaw (black jerseys) and Cracovia Krakow (striped jerseys) in 1936, which Polonia won 3–2; Władysław Szczepaniak (middle) was captain of the national team and became one of the Figureureheads of the Polish resistance. (R. Gawkowski collection, Warsaw)

Figure 15.2: Wilhelm Gora, who was the midfield ‘engine’ of the Polish national team before the war, set up DTSG Krakow with the industrialist Oskar Schindler. (GiA Katowice)

Figure 15.3: The occupiers’ sports clubs staged their championships and cup matches in the Warsaw stadiums; Polish athletes were not allowed to use them. (R. Gawkowski collection, Warsaw)

Figure 15.4: Caricature about the first round of the football championship in the General Government; the Figureures represent the individual clubs: Heer, Luftwaffe, Reichspost, Ostbahn, Ordnungspolizei. (Warschauer Zeitung, 24/25 November 1940)

Figure 15.5: SA-Gruppenführer Ludwig Fischer, the governor of the Warsaw district, deported Polish football players to Auschwitz and had his men shoot on spectators; in 1947, he died on the gallows of Warsaw Mokotów prison. (SMH Konstancin)

Figure 15.6: Ernst Willimowski, Polish and German footballer from Upper Silesia, played twenty-two times for the Polish national team and eight times for the German←xiv | xv→ national team. (Deutsche Sport-Illustrierte, no. 42, 1942, front page)

Figure 15.7: Sign in the exhibition ‘White Eagles, Black Eagles. Polish and German Footballers in the Shadow of Politics’, Warsaw 2012. (Konrad Urban, Konstancin)

Herzog

Figure 17.1: Fans and players of FC Gloria Wupperbrück celebrate the top scorer Heini Gabler with an enormous laurel wreath and scarves decorated with swastikas in the Berlin Olympic Stadium. (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung, Wiesbaden)

Figure 17.2: Players celebrate after the FC Gloria Wupperbrück vs VfB Sportfreunde Dresden semi-final; on the wall hangs a portrait of the Reichssportführer Hans von Tschammer und Osten. (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung, Wiesbaden)

Figure 17.3: A Hitler portrait hangs opposite a team photo from the early days of FC Gloria in the team’s club house. (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung, Wiesbaden)

Figure 17.4: The beer garden in FC Gloria’s club house, run by ‘mother Kleebusch’. (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung, Wiesbaden)

Figure 17.5: As ‘club mother’, ‘mother Kleebusch’ caringly tends to the youth teams’ physical well-being. (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung, Wiesbaden)←xv | xvi→

Photo Credits

Matheja

Figures 1.1–1.5: Archive Der Kicker/kicker-sportmagazin.

Figure 6: Festschrift 100 Jahre DFB, p. 42.

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 510

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788744751

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788744768

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788744775

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781788744744

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13977

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (December)

- Keywords

- football under the Swastika political football myths amusement and war entertainment in the everyday culture of soldiers and civilians

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2018. XVIII, 510 pp., 48 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG